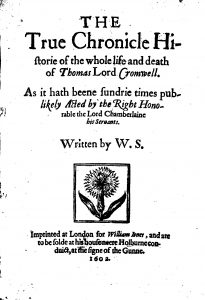

As we have seen, if Shakespeare was a play broker, his practice in this regard seems to have begun with a revised version of an old play (Locrine), just as Jonson describes with Poet-Ape. The historical record is of course imperfect; we do not know what is missing, what destroyed. But from the plays that are extant, the next to be published under Shakespeare’s initials was not for another seven years. 1602 saw the publication of Thomas Lord Cromwell, whose author is unknown and disputed. There is a marked step forward in the claim of its title page, for where Locrine was ‘edited, corrected and overseen’, Thomas Lord Cromwell was ‘written by W.S.’ The initials still allow for a degree of deniability. Had William Shakespeare been challenged on this claim of authorship, he could have denied that he was the ‘W.S.’ of the title page.

And of course, it might not be him; again, Wentworth Smith has been forwarded as the possible culprit, and the actor William Sly. But there are no records of William Sly ever authoring a play or even claiming to do so. Wentworth Smith at this time was fully engaged in writing plays for rival company the Lord Admiral’s Men and there is no evidence he wrote plays for anyone else. For if we accept that these apocryphal plays were supplied to publishers by our ‘W.S.’, Thomas Lord Cromwell’s title page bears another small but significant escalation; it tells prospective readers that the play has been ‘sundry times publicly acted by the Right Honourable Lord Chamberlain his Servants’. This play, in other words, was owned by Shakespeare’s company.

And of course, it might not be him; again, Wentworth Smith has been forwarded as the possible culprit, and the actor William Sly. But there are no records of William Sly ever authoring a play or even claiming to do so. Wentworth Smith at this time was fully engaged in writing plays for rival company the Lord Admiral’s Men and there is no evidence he wrote plays for anyone else. For if we accept that these apocryphal plays were supplied to publishers by our ‘W.S.’, Thomas Lord Cromwell’s title page bears another small but significant escalation; it tells prospective readers that the play has been ‘sundry times publicly acted by the Right Honourable Lord Chamberlain his Servants’. This play, in other words, was owned by Shakespeare’s company.

By the time of its publication, the following eight editions of seven plays had been published linking the name ‘William Shakespeare’ to the Lord Chamberlain’s Men:

- Richard II (1598): ‘As it hath been publicly acted by the Right Honourable the Lord Chamberlain his servants. By William Shake-speare.’

- Richard III (1598): ‘As it hath been lately acted by the Right honourable the Lord Chamberlaine his seruants. By William Shake-speare.’

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1600): ‘As it hath been sundry times publicly acted, by the Right honourable, the Lord Chamberlain his servants. Written by William Shakespeare.’

- 2 Henry IV (1600): ‘As it hath been sundry times publicly acted by the right honourable, the Lord Chamberlain his servants. Written by William Shakespeare.’

- Much Ado About Nothing (1600): ‘As it hath been sundry times publicly acted by the right honourable, the Lord Chamberlain his servants. Written by William Shakespeare.’

- The Merchant of Venice (1600): ‘As it hath been diverse times acted by the Lord Chamberlain his Servants. Written by William Shakespeare.’

- Richard III (1602): ‘As it hath been lately acted by the Right Honourable the Lord Chamberlain his servants. Newly augmented, by William Shakespeare.’

- The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602): ‘By William Shakespeare. As it hath been diverse times acted by the right Honourable my Lord Camberlaines servants. Both before her Majesty, and else-where.’

Given how strongly linked the Lord Chamberlain’s Men and the name ‘William Shakespeare’ had become, it seems reasonable that anyone picking up a copy of Thomas Lord Cromwell in 1602 would make the assumption that ‘W.S.’ was ‘William Shakespeare’. Who was behind this attribution?

As leading scholar Jonathan Bate points out in his introduction to William Shakespeare & Others, the identification of a play’s original acting company was a mark of authenticity as important as the playwright’s name. Addressing the problem of the apocryphal plays that have Shakespeare’s name or initials, in addition to the name of his company, Bate says:

He might have commissioned them. He might have polished up the raw scripts. As a key member of the company, he explicitly or implicitly signed them off for performance. He did not, as far as we are aware, disassociate himself or his company from them.

The question is whether a man who might commission or buy plays for a company, and perhaps ‘polish’ or adapt them, might have such a proprietorial feeling towards the final text that he might, without any difficulty of conscience, sell it as his own? That the authorship of this play has not been decided makes it likely it was a co-authored piece, with no single writer having dominance. As we have seen, a single authorial attribution was becoming important, as publishers were trying to position plays as a form of readable literature. It is clear from Henslowe’s diary that a play might be written by four of five different writers, working together. But a publisher didn’t want five names. They only wanted one. And in these circumstances, would it not be reasonable for the man who might be termed the commissioning editor, to offer his own?

This is not a unique idea. In our own times, artists such as Damien Hirst – or in an age closer to Shakespeare’s, Leonardo da Vinci – have sold works as their own that were in fact made by a cohort of makers working to the their direction. In academic publishing, a PhD supervisor (who has done no more than supervise) may get the chief writing credit despite not penning a word. And as previously mentioned, Hollywood screenwriting credits can be given to the person who originated the idea, or polished the idea, with other writers (who did the donkey work) sometimes getting no credit at all.

Peter Blayney, in his study of the play publishing business, makes the point that plays were not sufficiently profitable for publishers to seek them out. Plays would have been actively sold to a publisher.[1] The person best placed to do this in the case of a public play was not the author, but the owners of the script; the acting company whose stamp of authorisation is clearly printed on the title page of Thomas Lord Cromwell.

[1] Peter Blayney, ‘Publication of Playbooks’ in A New History of Early English Drama, eds. Cox and Kastan, p. 392.

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you about new content.