From Jonson’s description, the identity of Poet-Ape will clearly be a name with which scholars of early modern drama will be familiar, since this person has ‘grown to a little wealth, and credit in the scene.’ It is a writer, for his works are ‘the frippery of wit’. It has been suggested that this poem arose out of the so-called War of the Theatres, and is directed at either Thomas Dekker or John Marston. The War of the Theatres is the name given to the satirical feud that developed between Jonson on one side, and Dekker and Marston on the other, between 1599 and 1602. Jonson’s Poetaster, in which he first used the term ‘poet-ape’, was part of this feud. If Jonson is calling either Dekker or Marston ‘Poet-Ape’, he is presumably accusing them of being bad poets who recycle other people’s words.

It was common enough for writers to echo and in some cases even plagiarise parts of other people’s works, or even to write thinly-veiled copies of other people’s plays; there were no copyright laws, and theatres required a constant supply of new material. As Anna Bayman puts it in her study of Dekker’s prose pamphlets, ‘the habit of plagiarism and reuse of material was so commonplace that it could be considered orthodox literary practice’.[1] Though Dekker railed against derivative poets in his pamphlet The Wonderful Year (1603), calling upon the Muses to ‘banish these Word-pirates… into the gulf of Barbarism’ he was distinctly derivative himself. Jonson accused Dekker of plagiarism after the latter’s Satiromastix used one of Jonson’s characters (Tucca) from Poetaster.

Yet there is one word in Jonson’s epigram which means we must rule out Dekker’s being Jonson’s Poet-Ape, and that is the word ‘wealth’. According to the Dictionary of National Biography Dekker was ‘constantly shadowed by debt’ and occasionally overwhelmed by it. He was imprisoned for debt in 1598 and 1599, and then again in 1612, spending seven years behind bars after failing to repay £40 which he had borrowed from the playwright John Webster’s father.

So is John Marston Jonson’s target? He appears to have been a little wealthier, and Jonson had accused Marston (in the guise of the character Crispinus) of stealing his poetry in Poetaster, saying ‘hang him Plagiary’ (4.3.96). There is no evidence that Marston was a broker of any kind, but the accusation of ‘brokage’ need not mean that the target was a play-broker. John Marston twice used the word ‘broker’ in situations similar to Jonson’s epigram, and in those passages the term just means to recycle the ideas of others, or to pass them down second-hand. In Certain Satires I Marston writes of someone who ‘scornes the viol and the scraping stick, / And yet’s but Broker of another’s wit’. In The Scourge of Villainy we find someone ‘Who ne’er did ope[n] his Apish gurning mouth / But to retail and broke another’s wit.’ In other words, ‘brokage’ may refer to a lesser form of plagiarism, where ‘theft’ refers to the larger form. There is also nothing in the poem that suggests printed plays. Though the ‘sluggish gaping auditor’ who ‘marks not whose ’twas first’ could conceivably be an official of the stationer’s company who registered plays, ‘auditor’ also means ‘listener’.

There is an interesting echo in Jonson’s epigram of a scene in an anonymous play of the period, The First Part of the Return to Parnassus, which was performed at Cambridge university around 1601. In this play, a foolish young man named ‘Gullio’ ‘apes’ poets by quoting, according to a character called Ingenioso, ‘pure Shakespeare and shreds of poetry that he hath gathered at the theatres’, generally misquoting them. The final line of Jonson’s ‘Poet-Ape’ uses the same word, ‘shreds’, in the final line of his epigram: ‘shreds from the whole piece’. Ingenioso, like Jonson, refers to this practice as ’theft’: ‘O monstrous theft! I think he will run through a whole book of Samuel Daniel’s.’ He says this in response to a quote from Romeo and Juliet, interestingly associating Shakespeare’s play with misattribution.

REVERSION

So Jonson’s Poet-Ape could be someone who, like Gullio, quotes shreds of other people’s poetry and is (wrongly) thought by his listeners to be have originated those lines himself. This person is a figure on the theatre scene, whose works are witty. We are likely to have heard of him. Because he is wealthy, he cannot be Dekker, but could be Marston, whom Jonson had already accused of plagiarism and recycling (‘brokage’) There is just one sticking place; ‘Poet-Ape’ has bought plays. Jonson explicitly says that this is how he began: he would ‘buy the reversion of old plays’. Now you could argue that any aspiring playwright might buy plays in order to study how successful ones were constructed, but there is something about Jonson’s phrasing—buying ‘the reversion’ of a play—that suggests a different kind of buying; something more like a business transaction. A ‘reversion’ is a term from property law and is a future interest retained by the grantor when the lease expires. A reversion explains how a play might sometimes be performed by another company than the one that owned it. And to buy a ‘reversion’ of a play would mean that when that agreement expired, the play would belong to the new owner. We have no evidence that Marston bought old plays. His name does not appear on old plays that weren’t his. Shakespeare’s does.

Just because a piece of evidence doesn’t exist now, it doesn’t mean that it never did. But we can only argue from the evidence we have. Of course one can speculate that Marston bought the rights to old plays, but it is most unlikely. He was not a share-holder in an acting company. Indeed, very few writers held that particular position, and no-one considered a writer of note, except for Shakespeare. Perhaps there is another writer of ‘wealth and credit in the scene’ whose works were ‘the frippery of wit’, who ‘would [like to?] be thought our chief’ and who bought ‘the reversion of old plays’ but the only one for whom all the evidence exists is Shakespeare. He is documented as a theatre company shareholder, his grain-related and marriage negotiation activities suggest he involved himself in brokerage outside the theatre, Buck’s seeking his comment on the attribution of George A Greene (and the parallel comment from Juby) suggests he did so within the theatre, and — most critically — his name appeared on plays and poems that were not his.

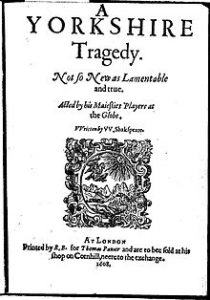

Which Elizabethan or Jacobean writers of note, active in the period 1590-1616, had works published under their names while they were alive which we know to be written by others? As far as I can ascertain, the only certain answer to that question is William Shakespeare. There is no other writer of the period who fits Jonson’s description so perfectly. Given the prominent role of Shakespeare’s father in the wool trade, Jonson’s final fleece metaphor could even be another identification mark. There is no better match for Jonson’s description, or indeed any notable writer of the period, besides Shakespeare, whose name was appended, as author, to works he didn’t write.

CONTINUED>>>

[1] Anna Bayman, Thomas Dekker and the Culture of Pamphleteering in Early Modern London, p.57

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you about new content.

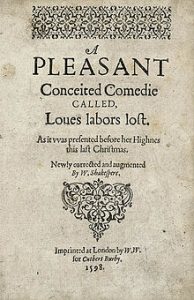

Now the difficult question must be asked. Many canonical plays had very similar title pages to the apocryphal plays. Locrine was ‘Newly set forth, overseen and corrected, / By W.S.’. Between 1598 and 1604, five different quartos were published with claims that the plays involved were edited (four of them explicitly by Shakespeare) for publication. In 1598, Cuthbert Burby published Love’s Labour’s Lost, ‘Newly corrected and augmented by W. Shakespere’. In 1599, Andrew Wise (who had already published Richard II and Richard III as ‘By William Shake-speare’) published 1 Henry IV as ‘Newly corrected by W. Shake-speare.’

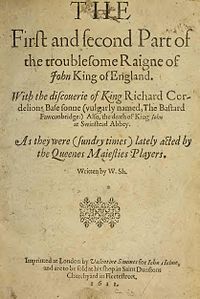

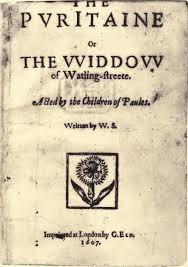

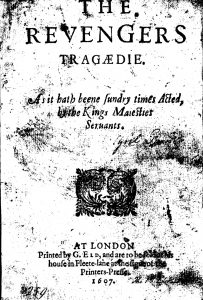

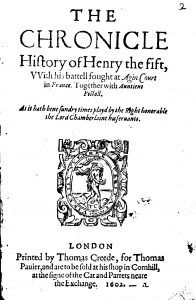

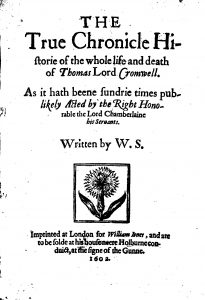

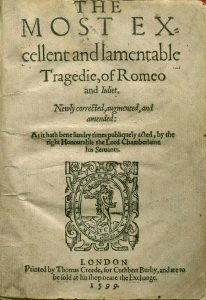

Now the difficult question must be asked. Many canonical plays had very similar title pages to the apocryphal plays. Locrine was ‘Newly set forth, overseen and corrected, / By W.S.’. Between 1598 and 1604, five different quartos were published with claims that the plays involved were edited (four of them explicitly by Shakespeare) for publication. In 1598, Cuthbert Burby published Love’s Labour’s Lost, ‘Newly corrected and augmented by W. Shakespere’. In 1599, Andrew Wise (who had already published Richard II and Richard III as ‘By William Shake-speare’) published 1 Henry IV as ‘Newly corrected by W. Shake-speare.’ In the same year, Thomas Creede (publisher of Locrine) printed the (still anonymous) Romeo and Juliet for Cuthbert Burby as ‘Newly corrected, augmented and amended’. In 1602, Creede printed a new edition of Richard III for Andrew Wise as ‘Newly augmented, by William Shakespeare.’ Nicholas Ling’s 1604 Hamlet stated it was ‘By William Shakespeare. Newly imprinted and enlarged to almost as much again as it was, according to the true and perfect Copy.’ Bearing in mind the possibility that Shakespeare was a play-broker who graduated from being the editor of works, to representing the works of others as his own, to what extent can we be sure that Shakespeare was the author of these plays?

In the same year, Thomas Creede (publisher of Locrine) printed the (still anonymous) Romeo and Juliet for Cuthbert Burby as ‘Newly corrected, augmented and amended’. In 1602, Creede printed a new edition of Richard III for Andrew Wise as ‘Newly augmented, by William Shakespeare.’ Nicholas Ling’s 1604 Hamlet stated it was ‘By William Shakespeare. Newly imprinted and enlarged to almost as much again as it was, according to the true and perfect Copy.’ Bearing in mind the possibility that Shakespeare was a play-broker who graduated from being the editor of works, to representing the works of others as his own, to what extent can we be sure that Shakespeare was the author of these plays?