In Shakespeare Beyond Doubt, it was stated without equivocation that ‘early modern authors did not ever pretend to be other people’.[1] Perhaps in the exact form it is expressed, that statement is true: neither of the best-known forms of attributional deception — employing a front, or agreeing to be a ghostwriter — could be described as ‘pretending to be other people’, exactly. But contrary to this confident assertion, we have evidence from the period that such arrangements did indeed take place. Writers in Shakespeare’s day sometimes wrote under false names and there is evidence some even used a ‘front’: a real person prepared to ‘play’ the author.

PLAGIARISM

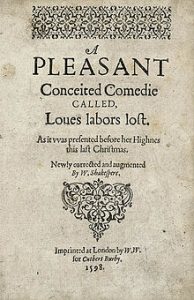

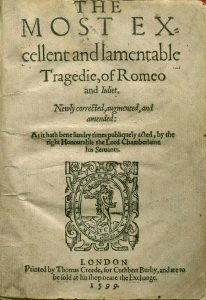

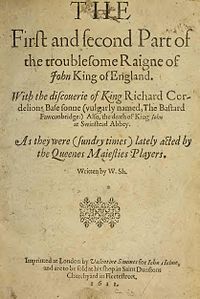

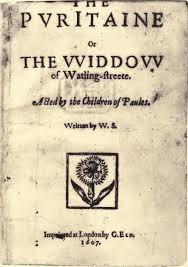

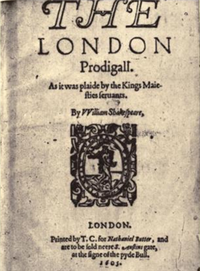

Putting one’s name on the work of another can take several forms. One form that this takes is plagiarism. Most Shakespearean scholars seem comfortable with the idea that Shakespeare began his career by adapting the work of others, and will even argue that he was accused of plagiarism by his contemporary, Robert Greene. They are not envisaging wholesale plagiarism of the type undertaken by the spy novelist Q.R. Markham. Rather they are imagining an adaptation process of the kind that might lead Shakespeare to turn The Troublesome Reign of King John into The Life and Death of King John, The Taming of A Shrew into The Taming of The Shrew. One might argue that exactly this kind of process might lead title pages to transition from ‘newly corrected and amended by W.S.’ to ‘written by W.S.’ but there, the dishonesty begins, and there most scholars prefer to jump off the train of thought and return to safety, agreeing that the works we know as Shakespeare’s are of unparalleled genius and therefore Shakespeare the man is morally unassailable. But there is evidence from the era that in some cases a writer might deliberately engage someone to represent their work under his name.

SET HIS NAME TO THEIR VERSES

Robert Greene, in Farewell to Folly (1591), wrote of the practice of certain writers concealing their identities by what he called ‘underhand brokery’ or what we might understand nowadays as employing somebody to act as a ‘front’. He wrote that

Others….if they come to write or publish any thing in print, it is either distilled out of ballads or borrowed of Theological poets, which for their calling and gravity, being loth to have any profane pamphlets pass under their hand, get some other Batillus to set his name to their verses. [My emphasis.] Thus is the ass made proud by this underhand brokery. And he that cannot write true English without the aid of clerks of parish churches will need make himself the father of interludes.

‘Interludes’ is a 16th century term for stage plays. ‘Batillus’ was a mediocre poet who tried to claim some verses by Virgil as his own. Greene’s use of the name is a clear reference to misattribution, but in contrast to his Roman example, where ‘Batillus’ claimed a better writer’s verses without his consent, Greene says that certain writers of his time actually invite the modern Batillus ‘to set his name to their verses’. Why might anyone do such a thing, especially when the person in question is an ‘ass’ who ‘cannot write true English without the aid’ of parish clerks?

Greene says it is because they do not want to have their reputation—their ‘calling and gravity’— sullied by the ‘profane’ nature of what they have written. His testimony shows that an Elizabethan writer concealing their identity through the agency of another real person is not the ridiculous proposition that orthodox scholars suggest; to Greene it is a known practice. He refers to this practice as ‘underhand brokery’; a necessarily discreet business transaction aimed at protecting the identity of the author. There is, however, no ‘conspiracy’ required for this to occur; simply a handshake, and an exchange of a text and (most likely) some money.

COULD HE BE REFERRING TO SHAKESPEARE?

Though the comment about not being able to write without the help of clerks will remind non-Stratfordians of Shakespeare’s six shaky signatures, it is very unlikely that the ‘Batillus’ he writes about is Shakespeare. It would be another two years before ‘William Shakespeare’ appeared on any publication, and seven years before it appeared on a play. What this evidence supports is not the idea of Shakespeare as a front, but rather the general principle of identity concealment, even to the point of using, as your cover, someone of limited literacy skills. Though he may not respect the arrangement, Greene (like Jonson in his epigram) does not reveal anyone’s identity. It has been suggested that Anthony Munday was his target, because elsewhere in the same publication, he criticises the play Fair Em, but that attack is not related to this passage. From the playwright’s manuscript of John a Kent and John a Cumber, Munday could clearly ‘write true English without the aid of clerks of parish churches’. And in any case, nobody, not even a Batillus, ever set their name to Fair Em. We’re unlikely to be able to work out Greene’s target, and it is not too much of a leap to say that this was his intention. He and other writers of the age routinely concealed the identities of those they criticised, and the reason was very simple.

Though the comment about not being able to write without the help of clerks will remind non-Stratfordians of Shakespeare’s six shaky signatures, it is very unlikely that the ‘Batillus’ he writes about is Shakespeare. It would be another two years before ‘William Shakespeare’ appeared on any publication, and seven years before it appeared on a play. What this evidence supports is not the idea of Shakespeare as a front, but rather the general principle of identity concealment, even to the point of using, as your cover, someone of limited literacy skills. Though he may not respect the arrangement, Greene (like Jonson in his epigram) does not reveal anyone’s identity. It has been suggested that Anthony Munday was his target, because elsewhere in the same publication, he criticises the play Fair Em, but that attack is not related to this passage. From the playwright’s manuscript of John a Kent and John a Cumber, Munday could clearly ‘write true English without the aid of clerks of parish churches’. And in any case, nobody, not even a Batillus, ever set their name to Fair Em. We’re unlikely to be able to work out Greene’s target, and it is not too much of a leap to say that this was his intention. He and other writers of the age routinely concealed the identities of those they criticised, and the reason was very simple.

CONTINUED>>>

[1] Andrew Hadfield in Shakespeare Beyond Doubt, edited by Stanley Wells and Paul Edmondson, CUP 2013, 72.

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you about new content.

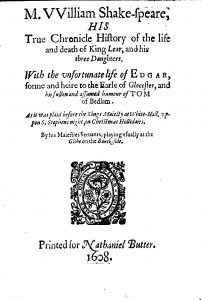

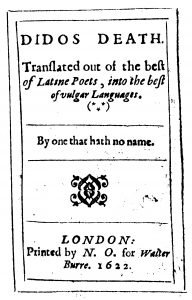

Many appeared in print under initials. Others works were published under obvious pseudonyms—Ignoto, Microcosmus—and sometimes less obvious ones, e.g. Andreas Philalethes. This practice continued well into the reign of King James I. As late as 1622, a publication called Dido’s Death bore the subtitle, ‘Translated out of the best of Latin poets into the best of vulgar languages. By one that hath no name.’ Printers and publishers, too, would often omit their names from title pages, or use only their initials. To disguise one’s identity, either partially or entirely, was a common precaution when publishing anything. Some writers clearly preferred not to have their names on their works.

Many appeared in print under initials. Others works were published under obvious pseudonyms—Ignoto, Microcosmus—and sometimes less obvious ones, e.g. Andreas Philalethes. This practice continued well into the reign of King James I. As late as 1622, a publication called Dido’s Death bore the subtitle, ‘Translated out of the best of Latin poets into the best of vulgar languages. By one that hath no name.’ Printers and publishers, too, would often omit their names from title pages, or use only their initials. To disguise one’s identity, either partially or entirely, was a common precaution when publishing anything. Some writers clearly preferred not to have their names on their works.