Actually engaging another person to stand in as the author is a step beyond the simple pseudonym, but Greene is not the only person whose testimony supports the idea that it occurred.

THE QUEEN SUSPECTS A FRONT

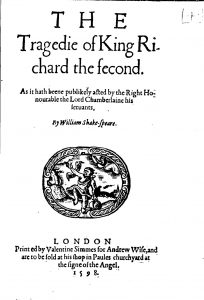

On 11 July 1599, historian John Hayward was brought before the Star Chamber to answer questions regarding his treatise The First Part of the Life and Raigne of King Henrie IV, which he had dedicated to the Earl of Essex. His book covered some of the same ground as Shakespeare’s Richard II (which had been published the previous year with his name on it): the deposition of a reigning monarch by an earl. According to a contemporary account, the Queen herself ‘argued that Hayward was pretending to be the author in order to shield ‘some more mischievous’ person, and that he should be racked so that he might disclose the truth’.[1]

In other words, the person then considered the highest authority in the land clearly believed that it was likely that someone might pretend to be the author of a work in order to shield someone else. Given the punishments she was known to mete out to writers (including the one she was threatening here) her surmise was not unreasonable. Of course one can argue that the punishments meted out to writers in the period were a very good reason why someone would not act as a front for someone else. Hayward was thrown into prison and remained there until 1602. But Robert Greene has knowledge of the practice and Elizabeth I suspects it; therefore it is safe to say that it occurred.

THE QUEEN AND SHAKESPEARE’S RICHARD II

There is also a small peculiarity to note with respect to the 1599 trial and imprisonment of John Hayward. He was prosecuted and subsequently imprisoned for writing about the Earl of Bolingbroke’s overthrow of the rightful king, Richard II, and for dedicating his book to the Earl of Essex, whom the queen was beginning to suspect intended to have her overthrown. A little over eighteen months later, in February 1601, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (Shakespeare’s company) were engaged by supporters of the Earl of Essex to perform Shakespeare’s Richard II on the eve of the Essex Rebellion. Essex would be tried and executed for treason before the month was out. Days after the rebellion had been quashed, and Essex and his followers (including the Earl of Southampton) imprisoned, a representative of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men was called to give evidence. That representative was not Shakespeare, but Augustine Phillips.

There is also a small peculiarity to note with respect to the 1599 trial and imprisonment of John Hayward. He was prosecuted and subsequently imprisoned for writing about the Earl of Bolingbroke’s overthrow of the rightful king, Richard II, and for dedicating his book to the Earl of Essex, whom the queen was beginning to suspect intended to have her overthrown. A little over eighteen months later, in February 1601, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (Shakespeare’s company) were engaged by supporters of the Earl of Essex to perform Shakespeare’s Richard II on the eve of the Essex Rebellion. Essex would be tried and executed for treason before the month was out. Days after the rebellion had been quashed, and Essex and his followers (including the Earl of Southampton) imprisoned, a representative of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men was called to give evidence. That representative was not Shakespeare, but Augustine Phillips.

He sayeth that on Friday last, or Thursday, Sir Charles Percy, Sir Jocelyn Percy, and the Lord Mounteagle, with some three more, spake to some of the players in the presence of this examinant to have the play of the deposing and killing of King Richard the Second to be played the Saturday next, promising to give them forty shillings more than their ordinary to play it. Where this examinant and his friends were determined to have played some other play holding that play of King Richard to be so old and so long out of use as that they should have small or no company at it But at their request this examinatant and his friends were content to play it the Saturday and had their 40 shillings more than the ordinary for it and so played it accordingly.

The prosecutor, Francis Bacon, was clear about the reason for this play being staged. Essex’s steward Sir Gilly Meyrick was ‘earnest to satisfy his eyes with the sight of that Tragedy which he thought soon his Lord should bring from the Stage to the State’.[2]

To non-Stratfordians, it seems peculiar that the author of this play, with its deposition scene, was neither questioned nor punished. His name, after all, was on the version that had been published in 1598. Though the queen had clearly felt threatened, and even enraged, by the earlier retelling of the same story which had been linked to the Earl of Essex, and the writer of that text had been thrown into prison (was still imprisoned at this time), neither she nor her advisors punished William Shakespeare for writing a play that had been used to justify sedition and threaten her life. Nor did she seem to bear any ill-will toward his company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, for they performed for her and her Court on the eve of Essex’s execution, only 17 days after they had staged Richard II for his followers.

THE QUEEN’S CONVERSATION WITH LAMBARD

Yet in August of the same year, she made a statement to her archivist, William Lambard, which demonstrates very well her understanding of Shakespeare’s play and how it was used to undermine her. The Queen had appointed Lambard in January 1600 as ‘the keeper of her records preserved in the Tower of London’.[3] On August 4 1601, he presented her personally with a document know as the Pandecta: a catalogue of all those records covering a period of 286 years, from the reign King John to that of Richard III. Lambard subsequently recorded their conversation and the delighted manner with which she received the results of his labours, and in this document, headed That which passed from the excellent Maiestie of Queene Elizabeth in her privie chamber at Eastgreenwich 4 August 1601. 43 regni sui towardes William Lambard, the following exchange is recorded.

Her Maiesty fell upon the reigne of R.2. saying

I am R.2. know you not that.

W.L: ‘such a wicked imagination was determined, & attempted, by a most unkind gentleman, the most adorned creature that ever your Maiesty made.’

Her Majesty: ‘he that will forget God will also forget his benefactors, this tragedy was forty times played in open streets & houses.’[4]

The reference to a tragedy ‘forty times played in open streets & houses’ must surely refer to Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Richard II. The authenticity of the Lambard conversation has been questioned, notably by Jonathan Bate, on the basis that the first record of it was printed only in 1780, and the original document has not survived.[5] But the words I have quoted above come from a far earlier transcript of the same conversation which has recently come to light, and this one has a very solid provenance.

The reference to a tragedy ‘forty times played in open streets & houses’ must surely refer to Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Richard II. The authenticity of the Lambard conversation has been questioned, notably by Jonathan Bate, on the basis that the first record of it was printed only in 1780, and the original document has not survived.[5] But the words I have quoted above come from a far earlier transcript of the same conversation which has recently come to light, and this one has a very solid provenance.

This early transcript, whose discovery was reported by Jason Scott-Warren in 2012, was copied out in the hand of Lambard’s son-in-law, Thomas Godfrey, in 1627.[6] Godfrey had married the archivist’s only daughter, Margaret Lambard, on 5 May 1609 at the church (fittingly) of St Katherine by the Tower. His transcript of the same conversation, presumably from papers in the possession of Lambard’s daughter, suggests the archivist’s conversation with the Queen was genuine.

Bate’s other chief objection, that Elizabeth cannot have read the Pandecta’s sixty-four pages aloud, was also answered by Scott-Warren. He noted that it depends upon ‘his assumption that ‘she descended from’ can be taken to mean ‘she read aloud’ when the phrases used in Lambard’s conversation (‘Then she proceeded to further pages’, ‘Then she proceeded to the Rolls’, ‘Then she came to the whole total of all the membranes and parcels aforesaid’) speak ‘less of laborious reading aloud, more of skimming.’[7]

Queen Elizabeth I understood very well the link between Shakespeare’s Richard II and the potential threat to her life. Why she didn’t have the author of this play prosecuted in the same manner as the author of the non-fiction version of the same story is hard to fathom. She had argued that Hayward was pretending to be the author in order to shield ‘some more mischievous’ person’ and wanted him racked to discover the truth. But she made no comment upon Shakespeare.

CONTINUE>>>

[1] Steve Sohmer, ’12 June 1599: Opening Day at Shakespeare’s Globe’, Early Modern Literary Studies 3.1 (1997): 1.1-46.

[2] Quoted in Jonathan Bate, Soul of the Age, 253.

[3] This is from an English translation of his Latin record of their meeting.

[4] These words are from the 1627 transcript. They differ only very slightly from the version published in 1780 e.g. ‘played 40 times’ vs ’40 times played’.

[5] Jonathan Bate, ‘Was Shakespeare an Essex Man?’, Proceedings of the British Academy, 162 (2009), 1-28, idem, Soul of the Age, 249-86.

[6] Jason Scott-Warren, ‘Was Elizabeth I Richard II?: The Authenticity of Lambarde’s ‘Conversation’’, Review of English Studies (2013) 64 (264): 208-230, first published online July 14, 2012, doi:10.1093/res/hgs062. The early transcript was recently discovered among the papers of Kent antiquarian Sir Edward Dering (1598-1644). Thomas Godfrey writes in a letter to Dering of their attempts to track down another copy of the Pandecta, which he believes was given by his late father-in-law to a friend Sir John Tindall, who had been murdered: ‘I have give you the best [light] of it that I can, & will not fail you in my best assistance to obtain it’.

[7] Jason Scott-Warren, ‘Was Elizabeth I Richard II?: The Authenticity of Lambarde’s ‘Conversation’’,re of skimming.” (Scott Warren, p.214)

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you about new content.

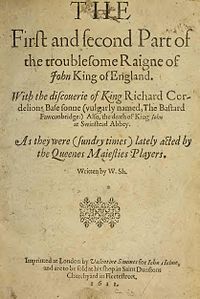

The title page stated it was played by Queen Elizabeth’s Men. But in 1611 a new edition was published by John Helme with the addition ‘Written by W. Sh’. In 1622, Thomas Dewes published a further edition, expanding the attribution to ‘W. Shakespeare’. A year later, the First Folio included a different King John, The Life and Death of King John, of which Troublesome Reign is acknowledged as a fore-runner and a source. Writers attributed with the authorship of Troublesome Reign include Christopher Marlowe, George Peele, Robert Greene and Thomas Lodge. Though it belonged to a rival company, it is possible that Troublesome Reign was bought by William Shakespeare and sold to John Helme as being his. Bearing in mind that this play dated from the early 1590s or even 1580s, we should recall that the ‘Poet-Ape’ of Jonson’s poem began his career in play-broking by buying ‘the reversion of old plays’ i.e. plays that were loaned out to another company. Thus the association with a different company does not rule out Shakespeare’s involvement in this transaction.

The title page stated it was played by Queen Elizabeth’s Men. But in 1611 a new edition was published by John Helme with the addition ‘Written by W. Sh’. In 1622, Thomas Dewes published a further edition, expanding the attribution to ‘W. Shakespeare’. A year later, the First Folio included a different King John, The Life and Death of King John, of which Troublesome Reign is acknowledged as a fore-runner and a source. Writers attributed with the authorship of Troublesome Reign include Christopher Marlowe, George Peele, Robert Greene and Thomas Lodge. Though it belonged to a rival company, it is possible that Troublesome Reign was bought by William Shakespeare and sold to John Helme as being his. Bearing in mind that this play dated from the early 1590s or even 1580s, we should recall that the ‘Poet-Ape’ of Jonson’s poem began his career in play-broking by buying ‘the reversion of old plays’ i.e. plays that were loaned out to another company. Thus the association with a different company does not rule out Shakespeare’s involvement in this transaction.