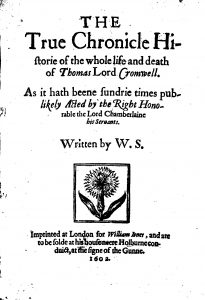

We are fortunate enough to possess, in the public archives, the reaction of someone who knew who wrote the play Locrine. The title page of a copy owned by George Buck (sometimes referred to as Buc), who in 1603 would be knighted and become James I’s Master of the Revels, bears the following hand-written inscription:[1]

Charles Tilney wrote a

Tragedy of this matter

he named Estrild: which

I think is this. it was lost

by his death. now some

fellow hath published it.

I made dumb shows for it.

which I yet have. G.B.

This note testifies that Buck’s late cousin Charles Tilney was the original author of Locrine. Tilney had been executed in 1586 for his part in the Babington Plot, so the play was at least a decade old by the time it was published. The text shows signs of revision; there are clear borrowings from Edmund Spenser which could not have been added in Tilney’s lifetime. Nevertheless Buck recognises the play as the one originally written by his cousin, a play for which Buck himself wrote the dumb shows — that is, sections of the drama to be acted without speaking. Observing that ‘some fellow’ has published it, he is keenly aware that the fellow in question, one ‘W.S’, is not the author.

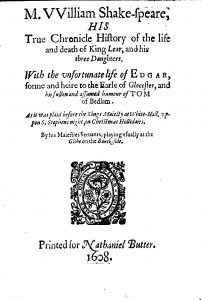

And this becomes particularly interesting when you consider that Buck is one of the very few people who record a conversation with William Shakespeare. Stratford neighbour Richard Quiney mentions in a letter that Shakespeare is thinking of buying tithes; his lodger Thomas Greene records in his diary conversations with his landlord about enclosing common land, and Thomas Heywood apparently has words with him about his name being on the title page of a collection of poems which include Heywood’s; but George Buck talks to him about the authorial attribution of a play.

The play in question is George A Greene, The Pinner of Wakefield. At the time Buck scribbled on his copy of Locrine, he did not apparently know the identity of the person who had ‘overseen and corrected it’; that person was just ‘some fellow’. Given his personal connection with the play, however, it seems reasonable that he might have made enquiries to discover who that ‘fellow’ was. And when, a few years later, he acquired an anonymous 1599 copy of George A Greene, and wondered who the author might be, it appears that the first person he sought out to ask was William Shakespeare. On the title page he noted:[2]

Written by …………. a minister who acted

the pinners part in it himself. Teste W. Shakespeare

And beneath this,

Ed. Juby saith that this play was made by Robert Greene.

James Shapiro describes this as Buck’s ‘flesh and blood encounter with a man he knew as both actor and playwright’ but in fact we have no idea whether Buck knew Shakespeare as an actor or a playwright. What seems much more likely is that he approached Shakespeare for this information because he knew that Shakespeare bought and sold plays. Had he, as seems likely, been curious as to the identity of the ‘fellow’ who published his cousin’s play, it is Shakespeare in a play-broking role that he would have uncovered.

The person from whom he seeks a second opinion, Edward Juby, was an actor and occasional playwright, but what seems more pertinent here is that Juby bought plays for the Admiral’s Men. Of all the people Buck might approach for information, he must have been aware that the people most likely to know would be the company play-brokers. That Juby was the documented play-broker of the Admiral’s Men surely increases the likelihood that Shakespeare was the play-broker for the Lord Chamberlain’s, given that Buck has asked them the same question.

But what of the answer? Though we cannot be entirely sure, the order of the inscriptions makes it probable that it was Shakespeare who was approached first. His unsatisfactory answer is reminiscent of his Belott-Mountjoy testimony; a selective or defective memory fails to supply the author’s name, for which Buck leaves a blank to be filled. His answer is also distinctly implausible: a minister of the church would not be suffered to act on the public stage, and Buck would know this.[3] None the wiser after seeking Shakespeare’s opinion, Buck sought out Juby and gained a direct and clear answer: the author was Robert Greene, who had died in 1592. Scholars, studying the text of the play, have determined that Juby’s answer was correct. Shakespeare’s answer, in the light of this, smacks of obfuscation. He didn’t know (or didn’t want to reveal what he did know), so he made something up.

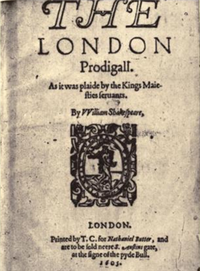

Buck was clearly very interested in correct authorial attribution. Two important conclusions can be derived from his title page inscriptions involving Shakespeare. Firstly, that the likelihood of his being the play-broker for the Lord-Chamberlain’s Men is increased by Buck’s approaching both him and the Admiral’s play-broking counterpart Juby. And secondly, that both title pages (Locrine and George A Greene) can be interpreted as linking Shakespeare with a practice of obfuscation and mis-attribution.

[1] This inscription is presented in modern spelling, with contractions and errors corrected. The edge of the title page is damaged, meaning some words and parts of words have been lost, but the re-instated version is widely accepted. The original version is as follows (with missing text bracketed):

Char. Tilney wrot[e a]

Tragedy of this mattr [which]

hee named Estrild: [which]

I think is this. it was [lost?]

by his death. & now s[ome]

fellow hath published [it.]

I made du[m]be shewes for it.

w[h]ch I yet haue. G. B.

[2] Again, the spelling has been modernised, and missing letters restored.

[3] This play was certainly a public play. Henslowe’s diary records its performance on five separate occasions, by Sussex’s Men, from 29 Dec 1593 to 22 Jan 1594.

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you about new content.