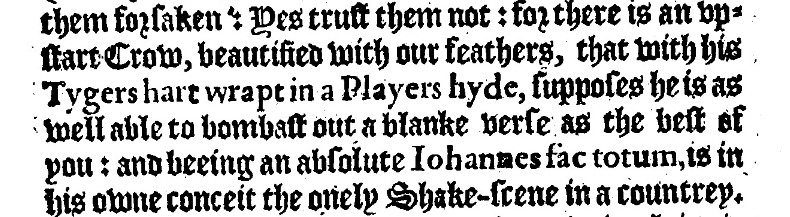

The outcry that followed the publication of A Groatsworth of Wit—which not only attacked actors but had accused three leading writers of scurrilous behaviour, including (dangerously in these times) atheism—led to Henry Chettle, who had shepherded the work into print ‘at his peril’, issuing an apology before the year was out. Though his prologue to Kind-Heart’s Dream is still widely referred to as ‘Chettle’s apology to Shakespeare’, it is nothing of the sort; not even if you believe that Shakespeare is the upstart Crow.

Biographers are rather attached to the idea that the apology is aimed at Shakespeare, because in issuing the apology, Chettle says a number of pleasant things about one of the people he has upset: that he himself had ‘seen his demeanour no less civil than he excellent in the quality he professes’ and that

‘diverse of worship [i.e. several important people] have reported his uprightness of dealing, which argues his honesty, and his facetious grace in writing, that approves his art’.

There is so little we know about Shakespeare the man, so little personal testimony as to his character, that we are naturally hungry for that gap to be filled. So deep is the need that biographers unconsciously ignore basic logic in order to use Chettle’s words as some kind of biographical hardcore.

IT’S ILLOGICAL, CAPTAIN

In 1998, Lukas Erne was the sixth scholar since 1874 to point out that Henry Chettle’s apology to one of the playwrights who took offence at the contents of Groatsworth of Wit cannot have been aimed at Shakespeare.[1] Chettle describes how the letter in Groatsworth, ‘written to diverse play-makers, is offensively by one or two of them taken’, and then apologises to one of these two, but not the other. Shakespeare cannot be the subject of his apology, since he is not among the group of playmakers, but (supposedly) one of the actors they are being warned about.

Scholars have argued that the two subjects of Chettle’s apology must be Marlowe and Shakespeare because neither George Peele nor Thomas Nashe would have reason to take offence at Groatsworth. Erne demonstrates this is not so: George Peele was a director of courtly pageants and an established poet with a reputation to defend, and it is unlikely he would have appreciated being called upon to ‘despise drunkenness’, ‘fly lust’, and ‘abhor those Epicures, whose loose life hath made religion loathsome to your ears’.

The second defence of Kind Heart’s Dream as an apology to Shakespeare relies upon the false premise that the word ‘quality’ in the phrase ‘the quality he professes’ refers specifically to acting. Of the four instances the OED cites in the period 1590-1630 for ‘quality’ meaning ‘profession, occupation or business’, only one of them refers to acting, and when Shakespeare uses ‘quality’ to refer to a profession in The Two Gentlemen of Verona, the ‘profession’ in question is outlawry.[2]

WHY DOES THIS READING PERSIST?

The commonly held belief that Chettle’s apology is to William Shakespeare is based on an implausible and illogical reading of the text, yet it continues to persist, despite the best efforts of Erne and others before him, for a reason Erne well understands: Shakespearean biography is so bereft of evidence of Shakespeare’s existence on the London literary scene that it cannot afford to abandon any apparent allusion to Shakespeare, even one that doesn’t bear scrutiny.

‘If we authenticate it,’ says Erne, ‘we have found a crucial milestone on Shakespeare’s artistic and social trajectory. If we don’t, a biographer writing his chapter on Shakespeare’s first years as an actor and dramatist is deprived of one of his most important narrative supports’.

Though prominent Shakespearean Brian Vickers has accepted that Chettle’s apology was not to Shakespeare, most Shakespearean biographers and scholars, desperately in need of meaningful content, have continued to pretend that it was.

In summary, Chettle’s apology is not to Shakespeare, and the upstart Crow is very likely not Shakespeare either, but with the accretion of time and authoritative repetition, both assumptions have hardened into accepted ‘facts’ and essential props of Shakespearean biography that cannot safely be removed lest the roof cave in. Yet the continued reliance on these props by orthodox scholars, and the seeming unwillingness of most of them to question or re-evaluate the evidence, only emphasises the inherent weakness of the orthodox position. The alternative is described by Lukas Erne:

‘Stripping bare our image of Shakespeare of four centuries of (mis-)interpretation is hermeneutically impossible. If it were possible, the results of a biographer might be less than rewarding, both aesthetically and economically. Some of the evidence which generations of Shakespeareans have hardened into fact would become ambiguous, riddled with difficulties. The figure we seem to know might take on shady contours and the character hidden behind it would become difficult to relate to.’ [3]

It sounds very much like the Shakespeare authorship question.

With Chettle’s apology removed, and the upstart Crow under a serious question-mark, it is time to start reviewing what evidence we have that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon was known as a writer.

[1] Lukas Erne, ‘Biography and Mythography: Rereading Chettle’s Alleged Apology to Shakespeare’, English Studies Vol 79, 1998, p.435.

[2] The Two Gentlemen of Verona, IV.i.56.

[3] Lukas Erne, op cit, p.439.

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you about new content.