The late 16th and early 17th century was a dangerous age in which to be a writer in England. There was no such thing as freedom of speech. Those who wrote works that upset others (particularly if those others were powerful, or had powerful friends) could easily find themselves in prison, and worse. A famous example is that of John Stubbs, who in 1579, when Shakespeare was just 15, published his opinions about the Queen’s proposed marriage to the Duke of Anjou and Alençon in a pamphlet entitled The Discovery of a Gaping Gulf. In this pamphlet he argued that the queen, at forty-six, was too old to have children, making the marriage pointless. The Queen was incensed and John Stubbs was arrested, along with his publisher William Page and his printer Hugh Singleton. On 13 October all three were found guilty and were sentenced to have their hands cut off. Hugh Singleton, being very elderly, had his sentence rescinded but both John Stubbs and William Page had their right hands cut off in the market place in Westminster on 3 November. It took three blows to sever Stubbs’s hand.

If this penalty was particularly severe, it was nevertheless a strong indication that writing was a dangerous business. Despite peddling fictions, the writers of plays were not exempt. Though Shakespeare’s era has long been depicted as a Golden Age of wit and manners, writers of that era were living under a repressive regime. Those in power were extremely conscious of the power of words to influence opinion and were paranoid about being criticised, mocked, or satirised. A number of the age’s most successful writers felt the sharp end of this particular stick.

Ben Jonson was arrested and imprisoned for a play he co-wrote with Thomas Nashe, The Isle of Dogs (1597). We have no idea why because all copies of the play have been destroyed. He was questioned by the Privy Council about his portrayal of political corruption in Sejanus (1603) and was imprisoned again, along with co-author George Chapman, for offending King James I with an anti-Scottish reference in Eastward Ho (1605). The other author of Eastward Ho, John Marston, fled to escape imprisonment. Ben Jonson reported later that they were threatened with having their noses and ears cut off. Though in this case they were reprieved, physical punishments were a very real possibility.

Satirist Thomas Nashe was another popular and successful writer. The only known portrait of him is a woodcut that shows him as a prisoner, with his legs chained together. He was imprisoned for writing Christ’s Tears Over Jerusalem, which offended the powers-that-be with a satirical portrait of London. Presumably his time in prison was not something he wished to repeat; endangered as a co-author of the Isle of Dogs, he escaped to the country when Ben Jonson was arrested. His house was raided in his absence and he remained away from London, effectively exiled in Norfolk.

Satirist Thomas Nashe was another popular and successful writer. The only known portrait of him is a woodcut that shows him as a prisoner, with his legs chained together. He was imprisoned for writing Christ’s Tears Over Jerusalem, which offended the powers-that-be with a satirical portrait of London. Presumably his time in prison was not something he wished to repeat; endangered as a co-author of the Isle of Dogs, he escaped to the country when Ben Jonson was arrested. His house was raided in his absence and he remained away from London, effectively exiled in Norfolk.

The Bishops’ Ban

Two years later in 1599, his name featured prominently on The Bishops’ Ban. Issued jointly by the Archbishop of Canterbury (the chief censor of publications) and the Bishop of London, this was a list of books to be banned and brought to Stationer’s Hall to be burnt. In what has been described as ‘the most sweeping and stringent instance of early modern censorship’, a number of individual titles were named, chiefly satires, and all histories and plays not specifically licensed. The final line of the ban targeted everything Thomas Nashe had written and would write in future:

That all NASHes books and Doctor HARVEYs books be taken wheresoever they may be found and that none of their bookes be ever printed hereafter.

The other person whose entire oeuvre was outlawed in the Bishops’ Ban was respected scholar Gabriel Harvey. He, too, had been imprisoned for his writing. In Three Letters, a published correspondence between him and the poet Edmund Spenser, he had referred unflatteringly to someone he referred to as Spenser’s ‘old controller’. The Controller of the Household, Sir James Croft, took this to be a reference to himself and had Harvey thrown in the Fleet Prison until Harvey managed to convince the Privy Council that he had, in fact, been referring to someone else (who was conveniently dead).

TORTURE IN BRIDEWELL

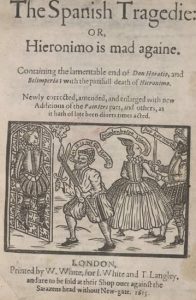

One didn’t even have to publish a work to be at risk. Playwright Thomas Kyd, author of a very successful and popular revenge tragedy, was arrested in the wake of government anger about what is now known as the Dutch Church libel; a poem, written in the style of his former room-mate, Christopher Marlowe, which had been posted on the wall of a church frequented by Huguenot immigrants. The Privy Council had sanctioned the use of torture to discover the author of the poem. Though the author wasn’t Kyd, he never recovered from his treatment in Bridewell prison and died the following year. Christopher Marlowe was arrested soon after and released on bail, apparently being killed in a fight just ten days later.

One didn’t even have to publish a work to be at risk. Playwright Thomas Kyd, author of a very successful and popular revenge tragedy, was arrested in the wake of government anger about what is now known as the Dutch Church libel; a poem, written in the style of his former room-mate, Christopher Marlowe, which had been posted on the wall of a church frequented by Huguenot immigrants. The Privy Council had sanctioned the use of torture to discover the author of the poem. Though the author wasn’t Kyd, he never recovered from his treatment in Bridewell prison and died the following year. Christopher Marlowe was arrested soon after and released on bail, apparently being killed in a fight just ten days later.

It would be no wonder if, under such a regime, some writers were perfectly happy for their works to be published anonymously, or to even bear the names of other people. Thus we should not necessarily judge it a terrible thing if Shakespeare published works under his name that were not his own. In Thomas Heywood’s case, this was clearly without the author’s permission. But Robert Greene says explicitly that this is a service that some writers sought out.

It is interesting how resistant mainstream scholarship is to this idea. When I discussed Greene’s statement with another scholar he insisted that Greene is referring to a poor or mediocre writer (‘Batillus’) trying to appear competent by engaging the services those who can write (i.e. parish clerks). But this is not what Greene says. If you don’t believe me, read the passage for yourself. When Greene says certain poets ‘get some other Batillus to set his name to their verses’ they are not engaging a scribe; they are persuading someone else to put his name on their work in order to avoid being publicly associated with something profane. Greene’s text is strong evidence that some writers used fronts in this period.

It is interesting how resistant mainstream scholarship is to this idea. When I discussed Greene’s statement with another scholar he insisted that Greene is referring to a poor or mediocre writer (‘Batillus’) trying to appear competent by engaging the services those who can write (i.e. parish clerks). But this is not what Greene says. If you don’t believe me, read the passage for yourself. When Greene says certain poets ‘get some other Batillus to set his name to their verses’ they are not engaging a scribe; they are persuading someone else to put his name on their work in order to avoid being publicly associated with something profane. Greene’s text is strong evidence that some writers used fronts in this period.

1590s ENGLAND / 1950s AMERICA

That this practice might have arisen in the Elizabethan era should not surprise us. Similar human situations spawn similar strategies. We know that writers in at least one other repressive and politically paranoid era, finding pseudonyms not sufficiently protective or effective, co-opted real individuals to act as their fronts. The parallel can be found in 1950s Hollywood.[1]

Under McCarthyism, writers with suspected communist sympathies began to be hauled up in front of the House Un-American Activities Commission and questioned about their political affiliations. Writers found to be communist sympathisers were black-listed, meaning they could no longer work as screenwriters for the big studios. Those who refused to name other communist sympathisers were jailed. In order to get around the prohibitions, certain black-listed writers secretly engaged people prepared to represent screenplays they had not written as their own. Woody Allen’s The Front depicts the possibly comedic repercussions of such a practice, but the realities were distinctly unfunny.

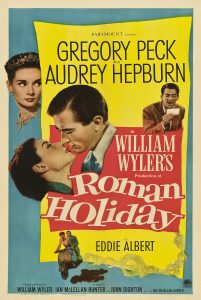

One might imagine that such an arrangement would be impossible to maintain if the hidden writer were famous, or their work became a high profile success, but history shows that this is not the case. In 1953, the Oscar for Best Screenplay went to the romantic comedy Roman Holiday, starring Audrey Hepburn, and was awarded to the supposed screenwriter Ian McLellan Hunter. But the author of Roman Holiday’s screenplay was actually Dalton Trumbo. It is now known that from 1947 (when he became one of the ‘Hollywood Ten’) to 1960, Dalton Trumbo wrote or co-wrote seventeen screenplays for which he received no writing credit.

One might imagine that such an arrangement would be impossible to maintain if the hidden writer were famous, or their work became a high profile success, but history shows that this is not the case. In 1953, the Oscar for Best Screenplay went to the romantic comedy Roman Holiday, starring Audrey Hepburn, and was awarded to the supposed screenwriter Ian McLellan Hunter. But the author of Roman Holiday’s screenplay was actually Dalton Trumbo. It is now known that from 1947 (when he became one of the ‘Hollywood Ten’) to 1960, Dalton Trumbo wrote or co-wrote seventeen screenplays for which he received no writing credit.

In Trumbo’s case the historical record has now been corrected, thanks to enormous efforts on his behalf by his son, and by the Writers Guild of America. However, there are still numerous works from the era that remain wrongly ascribed to their fronts. Alan Wald, professor of English and author of Writing from the Left, says that the writers who had employed fronts

were often in the difficult situation of having other people sign legal documents and even accept awards; thus, to reveal the names of fronts, even decades later, could bring lawsuits. However, it is now known that black radical novelist John O. Killens ‘fronted’ for blacklisted Abraham Polonsky in the important anti-racist film noir Odds Against Tomorrow. One former Communist who wrote Classics Comics in the 1950s made me promise never to reveal his identity.[2]

Even though some of the people who know the truth are still alive, the identity of many of these hidden writers will never be publicly known. Bear in mind that in these cases the truth remains unknown despite the fact that these deceptions occurred in an era of telephones, recording devices, and general literacy. How much more difficult to retrieve the truth about writers’ identities from 400 years ago?

Playwrights in 1590s England and screenwriters in 1950s Hollywood were in not dissimilar positions, in that they were trying to express ideas freely in a political landscape where the free expression of ideas was considered dangerous. The chief difference is that with Hollywood’s blacklisted writers only their livelihoods were at stake; for Elizabethan playwrights it was potentially their lives. For though being executed for your writing was a rare occurrence — one suffered nevertheless by religious writers Edmund Campion and John Penry — the conditions in Elizabethan prisons were sufficiently poor for a prison stay to become a death sentence. The poet and playwright Thomas Watson, a friend of Marlowe’s, seems to have died after being imprisoned. And of those writers mentioned above who fell foul of the authorities, three of them (Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe, Thomas Kyd) appear to have died, and certainly dropped out of sight, within a couple of years of being brought to account by the powers-that-be.

[1] These ideas were first explored at length in Daryl Pinksen’s Marlowe’s Ghost: The Blacklisting of the Man Who Was Shakespeare (2008).

[2] Professor Alan Wald, author of ‘Writing From the Left’, interviewed on : http://www.crimetime.co.uk/features/marxistnoir.php

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you about new content.