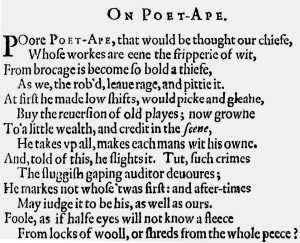

In 1616, the year of William Shakespeare’s death, the playwright and satirist Ben Jonson published his Works of Benjamin Jonson. In addition to his plays it contained his epigrams, including this one:

On Poet-Ape

Poor POET-APE, that would be thought our chief,

Whose works are e’en the frippery of wit,

From brokage is become so bold a thief,

As we, the robb’d, leave rage, and pity it.

At first he made low shifts, would pick and glean,

Buy the reversion of old plays; now grown

To a little wealth, and credit in the scene,

He takes up all, makes each man’s wit his own:

And, told of this, he slights it. Tut, such crimes

The sluggish gaping auditor devours;

He marks not whose ’twas first: and after-times

May judge it to be his, as well as ours.

Fool! as if half eyes will not know a fleece

From locks of wool, or shreds from the whole piece?

This poem, written during the time when William Shakespeare was active, tells a story. Let me share one interpretation of that story. Someone whom Jonson refers to as Poet-Ape has transitioned from being a play-broker to openly putting his name on other people’s plays. He began by buying ‘the reversion of old plays’ but now ‘makes each man’s wit his own’. This man, says Jonson, ‘would be thought our chief’. Chief what? Since Jonson was a poet and playwright, then presumably, chief writer of the period. It is not clear whether Jonson means that Poet-Ape ‘will be thought our chief’, which points towards Shakespeare, or that he has be pretensions to be thought of this way i.e. ‘would like to be thought our chief’, which might apply to anyone. But the person he is mocking is certainly involved in the theatre business, and has made a success of it and money out of it, according to Jonson.

A poet-ape is simply someone who apes a poet — mimics one, or pretends be one — but isn’t one. Many readers will, quite understandably, balk at the idea that the person he is calling Poet-Ape could possibly be William Shakespeare. Shakespeare is England’s national poet. How could someone like Ben Jonson, who referred to Shakespeare in the First Folio as ‘star of poets’, also refer to him as Poet-Ape? We are venturing here into the territory of the Shakespeare authorship question, and indeed this poem — never mentioned in conventional Shakespeare biographies — is a key exhibit for non-Stratfordians, those who doubt that William Shakespeare of Stratford upon Avon wrote the works attributed to him.

For Jonson to be referring to the same man as both ‘star of poets’ and ‘Poet-Ape’ is a contradiction too significant for many people to swallow. But Jonson’s conflicting opinions of Shakespeare, though frequently underplayed, are well known. In conversation with William Drummond, for example, he apparently said that ‘Shakespeare wanted art’. A number of orthodox scholars have accepted that Jonson lampooned Shakespeare in one of his plays, and in his private diaries, he appears to criticise him. We will return to the complexities of Jonson, but in the meantime, we should investigate whether Shakespeare is really the best fit for his ‘Poet-Ape’.

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you about new content.