The first defence against those who say Shakespeare didn’t write the works we know as his is simply this: his name is on the plays and poems attributed to him. William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon was a shareholder in the theatre company that performed Richard II, Richard III, Henry IV Part 2, The Merry Wives of Windsor, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant of Venice, Hamlet, King Lear and Pericles. Every one of these plays was published in his lifetime with both his name and the playing company printed on their title pages. His will, drafted and witnessed at Stratford-upon-Avon shortly before his death, bequeaths ‘to my fellows John Heminges, Richard Burbage, and Henry Condell, 26 shillings and 8 pence a piece to buy them rings’.[1] Heminges, Burbage and Condell were fellow shareholders in the King’s Men, formerly the Lord Chamberlain’s men. This line, like the famous bequest of ‘the second best bed’ to his wife is an interlineation; in essence, an afterthought. Nevertheless, he remembers his ‘fellows’, and thus firmly establishes that of all the William Shakespeares then living (and there were many, even in Warwickshire) it is he who was a ‘fellow’ of their theatre company and thus the attributed author of those plays.

All three of the men who Shakespeare names were actors; John Heminges was also the company’s financial manager. Seven years after Shakespeare’s death, Burbage had died, but Heminges and Condell wrote a letter prefacing Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, the First Folio of Shakespeare’s complete works, which attests to their knowing the man and receiving his manuscripts. ‘His mind and hand went together,’ they say, ‘and what he thought, he uttered with that easiness, that we have scarce received from him a blot in his papers’. Given his documented position as a ‘fellow’ of Heminges and Condell, shareholders in the theatre company that performed the vast majority of the thirty-six plays that were published under his name in the First Folio, this argument — his name is on the plays — seems to settle the matter.

The Apocryphal Plays

But the name William Shakespeare on a title page is not proof of authorship. In his lifetime, the name William Shakespeare, or the initials W.S., also appeared on a number of plays which we know were not written by the same person who wrote Othello and Hamlet. These plays, a key part of what is known as the Shakespeare apocrypha, include Locrine (1595), Thomas Lord Cromwell (1602), The London Prodigal (1605), The Puritan (1607), A Yorkshire Tragedy (1608) and The Troublesome Reign of King John (1611). The play Sir John Oldcastle may also have been published under Shakespeare’s name in his lifetime, though the only copy we have (dated ‘1600’) is from the ‘False Folio’ of 1619. In 1664, all seven of these plays were added to the Third Folio of Shakespeare’s works and remained part of the Shakespeare canon until they were removed by the more discerning scholars of the 18th century.

The vast majority of works in the 1623 First Folio were either not published in his life time, or were published anonymously; Henry V, Romeo and Juliet and three other canonical plays never bore his moniker.[2] To put it in perspective, someone scouring the bookstalls of St Paul’s churchyard for dramatic works by William Shakespeare in the year 1612 might find up to twenty; but only thirteen of them would be plays we now recognise as his.

The Apocryphal Poems

William Shakespeare was also declared as the author of various poems which were not written by the same person who wrote the Sonnets. A collection of poems called The Passionate Pilgrim published as being by William Shakespeare, first in 1599 and again in 1612, contained early drafts of two of Shakespeare’s sonnets (138 and 144) and three poems from Love’s Labour’s Lost. But it also contained poems by Christopher Marlowe, Sir Walter Raleigh, Richard Barnfield, Bartholomew Griffin, Thomas Heywood (in the second edition) and other unidentified writers. Certain scholars have argued strongly that A Lover’s Complaint, published as an appendix to Shake-speare’s Sonnets in 1609 with the clear attribution ‘By William Shakespeare’ was not by him. And whether or not that is his, A Funeral Elegy, published in 1612 under the initials ‘W.S.’, and argued to be Shakespeare’s by Donald Foster in the 1990s, is now known to be by John Ford.

‘Rogue Publisher’ Theory

The standard explanation for these non-Shakespearean works being published or registered under Shakespeare’s name or initials is that publishers were taking commercial advantage of his reputation, and this has been widely accepted. But subjected to closer scrutiny, this explanation raises a number of interesting questions. Not least of these questions is this: if Shakespeare’s name was being used by London publishers, without his permission, to represent work (often rather poor work) that was not his own, why did he not object? Thomas Heywood published a pointed objection letter when his poems were represented as Shakespeare’s in the 1612 edition of The Passionate Pilgrim, stating that the author under whose name his poems were published was also ‘much offended’. But if that was true, why had Shakespeare not voiced his objection as Heywood did? Heywood’s objection led to the name ‘William Shakespeare’ being removed from the title page. Why, if Shakespeare was really so offended, had he not asked for the same courtesy when it was first published thirteen years earlier?

An uncritical acceptance of the rogue publisher theory has led to some important considerations being overlooked. As an author, Shakespeare was extremely aware of the value of reputation. In both the plays and the sonnets, he writes repeatedly of the importance (and fragility) of one’s good name. In Othello, for example, Iago says:

Good name in man and woman, dear my lord,

Is the immediate jewel of their souls.

Who steals my purse steals trash. ’Tis something, nothing:

’Twas mine, ’tis his, and has been slave to thousands.

But he that filches from me my good name

Robs me of that which not enriches him

And makes me poor indeed.

Is it really possible that the writer of this passage genuinely wouldn’t care if other people’s work was published as if it were his own?

Coming at it from another angle, the rogue publisher theory does not sit well with the facts we have relating to William Shakespeare’s business dealings. A play was a company asset; Shakespeare was a shareholder of the company. Stratford-upon-Avon’s court records reveal that he would happily take a person to court to retrieve his property and seek damages. If official legal proceedings were not possible, Shakespeare had recourse to other actions. In the autumn of 1596, for example, one William Waite took out what nowadays would be known as a restraining order against Shakespeare and three others, using the common legal phrasing ‘ob metum mortis’ – ‘for fear of death’. The implication is that Shakespeare and the others named in the document had physically threatened him. Yet from 1598 to 1611, publishers printed both canonical and apocryphal plays under the name Shakespeare, seemingly without concern. If they were making money out of his name without his permission, why did he take no action of any kind against them? Is a better explanation simply that Shakespeare was behind the publication of all these plays?

“Careless about literary fame”

Until now, Shakespeare’s relationship to the spurious works published under his name has been understood as a symptom of his general lack of interest in publishing. Beyond the immediate requirements of writing plays for performance, Shakespeare, we are told, was unconcerned by the fate of his works. As early as 1821, antiquarian Edmund Malone wrote ‘We… can now pronounce with certainty that our poet was entirely careless about literary fame, and could patiently endure to be made answerable for compositions which were not his own, without using any means to undeceive the public’.[3] But this ‘certainty’ is no more than an assumption which arises from taking the rogue publisher theory as a fact.

Recent scholarly work radically undermines the much-cherished idea that Shakespeare cared nothing for literary fame. His very first publication, Venus and Adonis, is fronted by a quotation from Ovid’s Amores that makes a ‘claim to poetic immortality. Though the writer’s body will perish, the best part of him, his elite verses, will survive.’[4] Shakespeare’s sonnets also show us an author enormously preoccupied with this idea. No fewer than twenty-eight of his 154 sonnets address the issue of outlasting his mortal span through his works. And we should not imagine that, in foregrounding this theme, Shakespeare was merely following some kind of sonneteer’s protocol. James Blair Leishman, in his book on Shakespeare’s themes, noted that Shakespeare wrote ‘both more copiously and more memorably’ on the topic of poetry as immortalisation than any of his contemporaries. What Shakespeare reveals of his yearnings in the sonnets is very much at odds with the Shakespeare that scholars have been touting since the early nineteenth century as a man immune to the idea of fame. Shakespeare reveals himself in his sonnets as a man ‘obsessed with the transcendence of his own poetry.’[5]

Plays for Reading

Nor does it seem that Shakespeare intended that only his poetry be read and savoured. The idea that Shakespeare’s plays were written purely for performance is still very much in vogue, though it is counteracted by the existence of every Shakespeare play which has come down to us. These texts have only survived because publishing plays was profitable; because publishers knew plays had a readership entirely independent of that small minority who might wish to stage them. From the 1590 publication of Marlowe’s Tamburlaine onwards, prefatory material of printed plays makes it clear that they exist in different versions from their stage incarnations, and were aimed at a new literate class who composed a more sophisticated market than every-day playgoers. The length of many Shakespeare texts alone is enough to indicate that they were created for readers rather than performance. Documents of the era indicate plays ran for two to two and a half hours, and that longer texts were cut to meet these performance times. The full text of Hamlet runs to four and a half hours.

Plays Corrected

In his detailed study of Shakespeare’s publication record, Lukas Erne concludes that in the period 1594 to 1603 (i.e. from the time Shakespeare joined the Lord Chamberlain’s men as a shareholder, to the year they became The King’s Men), the pattern of publication suggests a concerted effort by Shakespeare and his company to publish each play within two years of its staging. According to Erne, every play from this period that could legally be published, was.[6] Several of these plays were published as having been played by Shakespeare’s company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men and were advertised on their title pages as ‘Newly corrected and augmented’ (or similar words) by Shakespeare. Heminges and Condell’s First Folio preface – which wishes ‘that the Author himself had lived to have set forth, and overseen his own writings’ – also implies that Shakespeare involved himself in such things.

Locrine

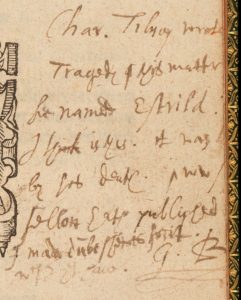

Is it possible, therefore, that the claim of Locrine – whose title page announces the play as ‘Newly set forth, overseen and corrected, / By W.S.’ – could be true, and have come directly from Shakespeare? Plays in his eras were the property of the theatre company who bought them, rather than their authors. Then as now, a play, once it had left the author’s hands, might be altered and adapted to suit the actors and performance space.

The idea that Shakespeare’s name and initials were used without his permission on the basis of his reputation holds no water in the case of Locrine. When the play was published in 1595, readers would not have known William Shakespeare as a dramatist. The only publications connected to his name at this point were the long poems Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. By the end of 1595, the only Shakespeare plays that had found their way into print were Titus Andronicus and the second two parts of Henry VI,[7] and all three had been published anonymously. If Thomas Creede’s intention was to publish Locrine under the initials W.S. on the basis that the public would be fooled into assuming it was by William Shakespeare, he could hardly be trading on Shakespeare’s reputation for dramatic excellence. In any case, if that were the intention, what was to stop him using the full name, rather than initials that might belong to another writer? The point is, Locrine doesn’t say it is ‘by W.S.’ It says it is ‘Newly set forth, overseen and corrected, / By W.S.’ This is a statement of editorship; it leaves the authorship of the piece open.

The London Prodigal and A Yorkshire Tragedy

Ten years later, when the name William Shakespeare had some dramatic clout, the title page of The London Prodigal did claim that it was ‘By William Shakespeare’. It also declared the play was ‘played by the Kings Majesties Servants’; the new name for the company in which Shakespeare was a shareholder. Similarly, 1608’s A Yorkshire Tragedy, apparently ‘Written by W. Shakspeare’, was ‘Acted by his Majesties Players at the Globe’. If the claims of Locrine had been tentative, the claims of these two plays were forthright in the extreme, declaring both authorship by Shakespeare and affiliation to The King’s Men.

Plays were a business asset of a theatre company. How did these plays come into the publishers’ hands from Shakespeare’s own company, with Shakespeare’s name on them, and with his company’s name on them? Was the process any different from the means by which Richard II and A Midsummer Night’s Dream were published, bearing identical claims? From the evidence of their other publications, can we conclude without question that the publishers involved were dishonest? Is there evidence that ‘Shakespeare’ had become a brand bearing minimal relationship to actual authorship? What might explain Shakespeare apparently not objecting to either the publishers themselves, or to the officials of Stationers Hall, where the ownership of publications was registered? Is it possible William Shakespeare himself sold these plays to the publishers, acting as a middle-man, or broker? These are the chief questions that must be addressed.

[1] In original spelling ‘to my fellowes John Hemynges, Richard Brubage [sic], and Henry Cundell, xxvj.s. viij.d. a peece to buy them ringes’. Throughout this book I have modernized spelling for ease of reading, except where I consider the original spelling is vital to the argument.

[2] Though in 1598, Francis Meres named Romeo and Juliet as being by Shakespeare, and extracts from the play featured in the poetic anthologies Belvedere and All England’s Parnassus in 1600 were also attributed to him.

[3] Boswell-Malone Shakespeare 1821 III p.329.

[4] Katherine Duncan-Jones and H.R.Woudhuysen (eds), Shakespeare’s Poems (2007), p.11.

[5] Lukas Erne, Shakespeare as Literary Dramatist (2003), p.6.

[6] Erne, p.86.

[7] Published as The First Part of the Contention Betwixt the Two Famous House of York and Lancaster and The True Tragedy of Richard Duke of York.

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you about new content.

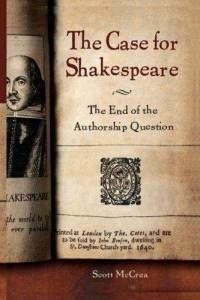

The more common position now is to deny that Hall and Marston are referring to Shakespeare’s poems. Scott McCrea in The Case for Shakespeare refutes the idea that the works Hall and Marston are referencing are Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. ‘Probably Hall had Samuel Daniel or Michael Drayton in mind,’ he says, without providing any evidence that their poetry had the specific features which Hall mentions. ‘In any case,’ he asserts ‘it wasn’t the Author [Shakespeare]’. This is his belief, but he has hardly proved it. McCrae only deals with those parts of the evidence that are easy to demolish, such as the idea that Marston’s ‘mediocria firma’ is a reference to Francis Bacon. He entirely ignores the critical passage about the ‘crafty cuttle’ who uses ‘another’s name’.

The more common position now is to deny that Hall and Marston are referring to Shakespeare’s poems. Scott McCrea in The Case for Shakespeare refutes the idea that the works Hall and Marston are referencing are Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. ‘Probably Hall had Samuel Daniel or Michael Drayton in mind,’ he says, without providing any evidence that their poetry had the specific features which Hall mentions. ‘In any case,’ he asserts ‘it wasn’t the Author [Shakespeare]’. This is his belief, but he has hardly proved it. McCrae only deals with those parts of the evidence that are easy to demolish, such as the idea that Marston’s ‘mediocria firma’ is a reference to Francis Bacon. He entirely ignores the critical passage about the ‘crafty cuttle’ who uses ‘another’s name’. The reason why orthodox scholars now deny that Hall and Marston are doubting Shakespeare’s identity (when some once accepted that they were) is because the very existence of sixteenth century doubt about the authorship of works published under the name William Shakespeare legitimises the authorship question. It also raises some significant and difficult questions. If William Shakespeare was as active and present on the London theatre scene at this time as is generally believed, why would his authorship be doubted? When Pygmalion and Virgidemiarum were published in 1598, Marston was establishing himself as a playwright and both Marston and Hall could presumably have confirmed the author’s identity for themselves were Shakespeare – as orthodox scholars assume – physically present and well-known on the London literary scene. What is more, Marston was from Warwickshire, Shakespeare’s home county. Indeed, Marston’s father was appointed counsel to the city of Coventry, and was lawyer to Thomas Green, solicitor to the corporation of Stratford-on-Avon, who has been described by orthodox Shakespearean scholar Dave Kathman as ‘one of Shakespeare’s closest friends in Stratford’. Green, who was a lodger in the Shakespeare household from 1603 to 1611, and who refers in his diary to ‘cousin Shakespeare’, was sponsored to enter the Middle Temple by John Marston and his father in 1595.

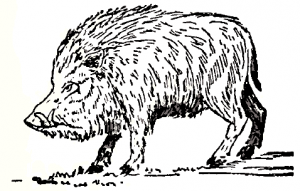

The reason why orthodox scholars now deny that Hall and Marston are doubting Shakespeare’s identity (when some once accepted that they were) is because the very existence of sixteenth century doubt about the authorship of works published under the name William Shakespeare legitimises the authorship question. It also raises some significant and difficult questions. If William Shakespeare was as active and present on the London theatre scene at this time as is generally believed, why would his authorship be doubted? When Pygmalion and Virgidemiarum were published in 1598, Marston was establishing himself as a playwright and both Marston and Hall could presumably have confirmed the author’s identity for themselves were Shakespeare – as orthodox scholars assume – physically present and well-known on the London literary scene. What is more, Marston was from Warwickshire, Shakespeare’s home county. Indeed, Marston’s father was appointed counsel to the city of Coventry, and was lawyer to Thomas Green, solicitor to the corporation of Stratford-on-Avon, who has been described by orthodox Shakespearean scholar Dave Kathman as ‘one of Shakespeare’s closest friends in Stratford’. Green, who was a lodger in the Shakespeare household from 1603 to 1611, and who refers in his diary to ‘cousin Shakespeare’, was sponsored to enter the Middle Temple by John Marston and his father in 1595. Let us summarise the evidence. Hall undoubtedly testifies that he suspects a contemporary author of using a front. The ‘crafty cuttle’ who uses ink as a defensive disguise, who likes to ‘complain of wronged faith or fame’, fame which he may shift onto ‘another’s name’, is surely too explicit a reference to deny. Marston paraphrases two lines from Venus and Adonis and alludes to Hall as a hunter of a famous boar – the poem’s motif. Hall’s critical assessment of Labeo’s poetry has seven points of specific correspondence with Shakespeare’s two poems that no other poet published in the years before 1597 can match:

Let us summarise the evidence. Hall undoubtedly testifies that he suspects a contemporary author of using a front. The ‘crafty cuttle’ who uses ink as a defensive disguise, who likes to ‘complain of wronged faith or fame’, fame which he may shift onto ‘another’s name’, is surely too explicit a reference to deny. Marston paraphrases two lines from Venus and Adonis and alludes to Hall as a hunter of a famous boar – the poem’s motif. Hall’s critical assessment of Labeo’s poetry has seven points of specific correspondence with Shakespeare’s two poems that no other poet published in the years before 1597 can match: This is the year in which William Shakespeare bought a load of stone in Stratford in January, and in the same month, was said to be interested in buying some local tithes. His Stratford grain-holding was assessed in February, and in October he was not found in his London lodgings when the taxman called, but that is as much as we can say about his whereabouts. This is also the year in which he would be listed, eighteen years later, as ‘principle comedian’ in the play Every Man in His Humour; an item of evidence we will assess more fully when we turn our attention properly upon Ben Jonson. The seeming doubt of Hall and the possible doubt of Marston leads to an important question. Exactly how visible on the London scene was William Shakespeare in the 1590s?

This is the year in which William Shakespeare bought a load of stone in Stratford in January, and in the same month, was said to be interested in buying some local tithes. His Stratford grain-holding was assessed in February, and in October he was not found in his London lodgings when the taxman called, but that is as much as we can say about his whereabouts. This is also the year in which he would be listed, eighteen years later, as ‘principle comedian’ in the play Every Man in His Humour; an item of evidence we will assess more fully when we turn our attention properly upon Ben Jonson. The seeming doubt of Hall and the possible doubt of Marston leads to an important question. Exactly how visible on the London scene was William Shakespeare in the 1590s?