Perhaps, despite the strong evidence that identifies Edward Alleyn as Robert Greene’s ‘Player’ and ‘Crow’, you are nevertheless persuaded that the upstart Crow is Shakespeare because he thinks himself ‘in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country’? Surely the similarity between ‘Shake-scene’ and ‘Shakespeare’ is too close to be a coincidence?

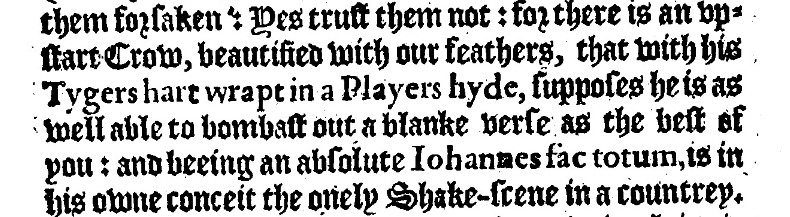

Yet the typography of the text counts against ‘Shake-scene’ meaning ‘Shakespeare’. Throughout Groatsworth, quotations, and most names, are printed in the much clearer italic lettering rather than blackletter, even the name ‘Johannes fac totum’. Epithets (such as ‘upstart Crow’) are not. Shake-scene is not in italic print, suggesting it is not a name, but a common noun. Being preceded by an article — ‘the… Shake-scene’ — points in the same direction; proper nouns (names) don’t need to be prefaced with ‘a’ or ‘the’.

SHAKE-STUFF

There was a similar word in use at the time: ‘shake-rag’, a term found in printed sources from 1571, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, for ‘a ragged disreputable person’. ‘It is no marvel that shakerags [L. sordidos homines] (which have no regard of honesty) did … rail without shame’ wrote Arthur Golding in his translation of Calvin’s The Psalms of David. Here are some more examples:

- ‘You totter’d shake-rag’d rogues, what domineer you?’ — Anon, A Larum for London (1602).

- ‘Pecunia, a name of one of the shake-rag goddesses in our fourth booke’ — St Augustine, tr. J.Healey, Of the City of God (1610).

- ‘If you ask but a shake-rag who he is, he will answer, that (at the least) he is descended from the Goths, & that his bad fortune hath thus dejected him’ — Juan de Luna, The pursuit of the historie of Lazarillo de Tormez (1622).

- ‘this shake-rag, this young impudent Rogue’ — Mateo Aleman, The Rogue (1623).

- ‘Do you talk Shake-rag: Heart yond’s more of ‘em. I shall be Beggar-maul’d if I stay’ — Richard Brome, A Joviall Crew (1641).

By adapting ‘Shake-rag’ (beggar) into ‘Shake-scene’ (actor), Greene could not only refer to the physical vigour with which an actor such as Alleyn would stride around the stage, shaking the scenery, but also hint at a certain disreputable quality associated with the original term.

A GRAMMATICAL TEST

If you want proof that ‘Shake-scene’ is not a proper noun, and does not stand for Shakespeare, try substituting one for the other: it makes no sense for Greene to accuse this actor of being ‘in his own conceit the only Shakespeare in a country’. It is simply another way for Greene to say ‘actor’ without repeating the words he has already used, as a substitution demonstrates: the upstart Crow is ‘in his own conceit the only actor in a country’.

The perceived ‘punning allusion to Shakespeare’s name’ is not proven and may not be there at all. As much as we might want Greene to be referring to Shakespeare, we should not leap upon the word Shake-scene for the mere fact that it begins with the same first syllable. Wishful thinking will lead us to see connections that the author never intended, and to identify the ‘Shake-scene’ [actor] as Shakespeare, when the main text of Groatsworth, and Greene’s previous writings, implicate Edward Alleyn, is no more valid than the tendency of some Oxfordians to see every use of the common English word ‘ever’ as an anagram pinpointing their candidate, Edward de Vere.

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you when there’s new content.