When the ‘Labeo’ material first came to light, some orthodox scholars accepted it as evidence that Hall and Marston had doubts about Shakespeare’s identity, but concluded they were simply mistaken. H.N.Gibson, who vigorously defends the traditional attribution of Shakespeare’s works, nevertheless says ‘We may agree that Hall is patting himself on the back because he thinks he has guessed the identity of an author writing under a pseudonym and collaborating with an inferior poet’.

The more common position now is to deny that Hall and Marston are referring to Shakespeare’s poems. Scott McCrea in The Case for Shakespeare refutes the idea that the works Hall and Marston are referencing are Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. ‘Probably Hall had Samuel Daniel or Michael Drayton in mind,’ he says, without providing any evidence that their poetry had the specific features which Hall mentions. ‘In any case,’ he asserts ‘it wasn’t the Author [Shakespeare]’. This is his belief, but he has hardly proved it. McCrae only deals with those parts of the evidence that are easy to demolish, such as the idea that Marston’s ‘mediocria firma’ is a reference to Francis Bacon. He entirely ignores the critical passage about the ‘crafty cuttle’ who uses ‘another’s name’.

The more common position now is to deny that Hall and Marston are referring to Shakespeare’s poems. Scott McCrea in The Case for Shakespeare refutes the idea that the works Hall and Marston are referencing are Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. ‘Probably Hall had Samuel Daniel or Michael Drayton in mind,’ he says, without providing any evidence that their poetry had the specific features which Hall mentions. ‘In any case,’ he asserts ‘it wasn’t the Author [Shakespeare]’. This is his belief, but he has hardly proved it. McCrae only deals with those parts of the evidence that are easy to demolish, such as the idea that Marston’s ‘mediocria firma’ is a reference to Francis Bacon. He entirely ignores the critical passage about the ‘crafty cuttle’ who uses ‘another’s name’.

Other orthodox responses have been as inadequate as McCrea’s. It has been argued that Labeo is Marston himself but this ignores both the specific qualities of the verse identified by Hall, and also the awkward fact that Marston writes about Labeo too (and not in a self-referencing manner). Others have suggested that Labeo is simply Hall’s term for any bad poet. But the reference to ‘this bawdy Poggies ghost’ is surely far too specific to stand for an archetype, and Marston put the words of Venus and Adonis directly into Labeo’s mouth.

The reason why orthodox scholars now deny that Hall and Marston are doubting Shakespeare’s identity (when some once accepted that they were) is because the very existence of sixteenth century doubt about the authorship of works published under the name William Shakespeare legitimises the authorship question. It also raises some significant and difficult questions. If William Shakespeare was as active and present on the London theatre scene at this time as is generally believed, why would his authorship be doubted? When Pygmalion and Virgidemiarum were published in 1598, Marston was establishing himself as a playwright and both Marston and Hall could presumably have confirmed the author’s identity for themselves were Shakespeare – as orthodox scholars assume – physically present and well-known on the London literary scene. What is more, Marston was from Warwickshire, Shakespeare’s home county. Indeed, Marston’s father was appointed counsel to the city of Coventry, and was lawyer to Thomas Green, solicitor to the corporation of Stratford-on-Avon, who has been described by orthodox Shakespearean scholar Dave Kathman as ‘one of Shakespeare’s closest friends in Stratford’. Green, who was a lodger in the Shakespeare household from 1603 to 1611, and who refers in his diary to ‘cousin Shakespeare’, was sponsored to enter the Middle Temple by John Marston and his father in 1595.

The reason why orthodox scholars now deny that Hall and Marston are doubting Shakespeare’s identity (when some once accepted that they were) is because the very existence of sixteenth century doubt about the authorship of works published under the name William Shakespeare legitimises the authorship question. It also raises some significant and difficult questions. If William Shakespeare was as active and present on the London theatre scene at this time as is generally believed, why would his authorship be doubted? When Pygmalion and Virgidemiarum were published in 1598, Marston was establishing himself as a playwright and both Marston and Hall could presumably have confirmed the author’s identity for themselves were Shakespeare – as orthodox scholars assume – physically present and well-known on the London literary scene. What is more, Marston was from Warwickshire, Shakespeare’s home county. Indeed, Marston’s father was appointed counsel to the city of Coventry, and was lawyer to Thomas Green, solicitor to the corporation of Stratford-on-Avon, who has been described by orthodox Shakespearean scholar Dave Kathman as ‘one of Shakespeare’s closest friends in Stratford’. Green, who was a lodger in the Shakespeare household from 1603 to 1611, and who refers in his diary to ‘cousin Shakespeare’, was sponsored to enter the Middle Temple by John Marston and his father in 1595.

John Marston therefore had solid Warwickshire and Stratford-on-Avon connections, and stood surety for ‘one of William Shakespeare’s closest friends’ three years before he published his satirical comment about Labeo. Of course, Kathman’s label for Thomas Green isn’t necessarily correct. And even if it were true by 1611/2 when Green first used the term ‘cousin’, the term was used somewhat loosely in the era, and we have no idea whether Green knew Shakespeare as early as 1598. Nevertheless one can’t help feeling that if the talented author of Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece was the Stratford man, John Marston would have been well-placed to know. It is no wonder, in the circumstances, that orthodox scholars find it difficult to look closely at this evidence or give the argument more than a dismissive wave of the hand.

THE CASE FOR DOUBT

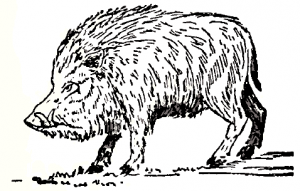

Let us summarise the evidence. Hall undoubtedly testifies that he suspects a contemporary author of using a front. The ‘crafty cuttle’ who uses ink as a defensive disguise, who likes to ‘complain of wronged faith or fame’, fame which he may shift onto ‘another’s name’, is surely too explicit a reference to deny. Marston paraphrases two lines from Venus and Adonis and alludes to Hall as a hunter of a famous boar – the poem’s motif. Hall’s critical assessment of Labeo’s poetry has seven points of specific correspondence with Shakespeare’s two poems that no other poet published in the years before 1597 can match:

Let us summarise the evidence. Hall undoubtedly testifies that he suspects a contemporary author of using a front. The ‘crafty cuttle’ who uses ink as a defensive disguise, who likes to ‘complain of wronged faith or fame’, fame which he may shift onto ‘another’s name’, is surely too explicit a reference to deny. Marston paraphrases two lines from Venus and Adonis and alludes to Hall as a hunter of a famous boar – the poem’s motif. Hall’s critical assessment of Labeo’s poetry has seven points of specific correspondence with Shakespeare’s two poems that no other poet published in the years before 1597 can match:

- ‘Heroic poesy’ – both Venus and Lucrece fall into this category.

- ‘Big But Ohs’ – both Venus and Lucrece have many lines starting But and Oh.

- Hyphenated epithets – common in both Venus and Lucrece.

- The poet implores Phoebus/Apollo to guide his enterprise (Venus and Adonis)

- The poet steals ‘whole pages’ from Petrarch (The Rape of Lucrece)

- The poems are sexual in nature (both Venus and Lucrece)

- ‘bawdy Poggies ghost’ – the poems are in Marlowe’s style (both Venus and Lucrece)

We can accept that Hall doubts the authorship of Shakespeare’s earliest published works without accepting that he was correct to do so. Whether Marston doubts Shakespeare’s authorship is less clear, since his reference to a ‘strange… metamorphosis’ is too ambiguous for us to be certain, but he doesn’t challenge Hall’s ‘crafty cuttle’ passage, and says nothing that would link Labeo to William Shakespeare of Stratford, despite being from the same county.

By 1598, when Marston’s The Metamorphosis of Pygmalion’s Image was published, orthodox scholars believe that William Shakespeare was the leading playwright for the Lord Chamberlain’s men, as well as being a shareholder and (at least occasionally) an actor. Most scholars think that by this time Titus Andronicus, all three parts of Henry VI, Richard II, Richard III, The Taming of the Shrew, The Comedy of Errors, Two Gentlemen of Verona, Love’s Labours Lost, Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant of Venice, and The Merry Wives of Windsor had all been written and staged. But if the authorship doubts of Marston and Hall are accepted as valid (and I have seen no convincing rebuttal), they surely cast some serious doubt on either Shakespeare’s visibility (in a physical sense) on the London literary scene in 1598, or his ability to convincingly pass as the author of these two narrative poems.

This is the year in which William Shakespeare bought a load of stone in Stratford in January, and in the same month, was said to be interested in buying some local tithes. His Stratford grain-holding was assessed in February, and in October he was not found in his London lodgings when the taxman called, but that is as much as we can say about his whereabouts. This is also the year in which he would be listed, eighteen years later, as ‘principle comedian’ in the play Every Man in His Humour; an item of evidence we will assess more fully when we turn our attention properly upon Ben Jonson. The seeming doubt of Hall and the possible doubt of Marston leads to an important question. Exactly how visible on the London scene was William Shakespeare in the 1590s?

This is the year in which William Shakespeare bought a load of stone in Stratford in January, and in the same month, was said to be interested in buying some local tithes. His Stratford grain-holding was assessed in February, and in October he was not found in his London lodgings when the taxman called, but that is as much as we can say about his whereabouts. This is also the year in which he would be listed, eighteen years later, as ‘principle comedian’ in the play Every Man in His Humour; an item of evidence we will assess more fully when we turn our attention properly upon Ben Jonson. The seeming doubt of Hall and the possible doubt of Marston leads to an important question. Exactly how visible on the London scene was William Shakespeare in the 1590s?

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you about new content.