Context matters. Careful scholars, rather than unquestioningly adopting ‘facts’ established by men in powdered wigs, should consider the exact context in which Robert Greene wrote Groatsworth in 1592.

THE THEATRE SCENE IN 1592

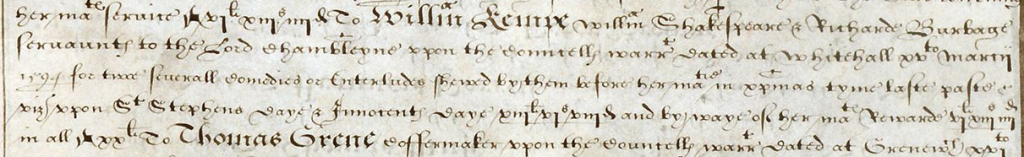

We have no evidence of William Shakespeare’s involvement in the London theatre scene at this time (the first evidence is dated two years later). He was not, like Edward Alleyn, a leading tragedian of the scene-shaking variety. If he was acting before 1594, it must have been in very minor roles, since there are no reports of him. Nor is there any evidence he was known, even among playwrights, as a writer of plays. Two plays now thought to be his (the fore-runners of Henry VI Parts 1 and 3) were first mentioned in 1592, but as we’ve seen, their authorship has been disputed by orthodox scholars. In 1594, two years after Groatsworth, the first plays of the Shakespeare canon were published, but not with his name on.

No-one had mentioned Shakespeare before Robert Greene, and let’s not forget that Greene doesn’t mention Shakespeare either. This is a possible allusion, not a factual reference. In the rest of Groatsworth, Green’s complaint against a certain actor (The Player) seems to be directed at Edward Alleyn. In his earlier work Francesco’s Fortunes his complaint against actors is also directed at Alleyn, and compares him to the crow beautified with other’s feathers. Is it really likely that the complaint against an actor comparing him to that same crow in the Groatsworth letter is about anyone other than Alleyn?

GREENE’S CIRCUMSTANCES IN 1592

Greene has no documented link to Shakespeare, but has a documented relationship with Alleyn. When he wrote Groatsworth, he knew he was dying, and dying in poverty. By contrast, Edward Alleyn was wealthy and successful, thanks to the wit and words of Greene and his fellow playwrights. The orthodox reading is that Greene, with his dying words, takes a jealous swipe at an up-and-coming playwright no-one has heard of, but this would hardly be a dying man’s concern.

His chief concern, which he could hardly make more obvious, is the disparity of wealth between successful actors (‘those puppets that spake from our mouths’) and the poverty-stricken gentleman scholars (chiefly himself) who ‘spend their wits making plays’, supplying the actors with the source of their riches and fame. From its title (A Groatsworth of Wit, Bought With A Million of Repentance), through its main text, to its accompanying letters, the focus of Groatsworth is on money, and specifically on the comparatively low monetary value placed on the ‘wit’ of Greene and his fellow writers, despite the fact that it provides actors with their entire living.[1]

His chief concern, which he could hardly make more obvious, is the disparity of wealth between successful actors (‘those puppets that spake from our mouths’) and the poverty-stricken gentleman scholars (chiefly himself) who ‘spend their wits making plays’, supplying the actors with the source of their riches and fame. From its title (A Groatsworth of Wit, Bought With A Million of Repentance), through its main text, to its accompanying letters, the focus of Groatsworth is on money, and specifically on the comparatively low monetary value placed on the ‘wit’ of Greene and his fellow writers, despite the fact that it provides actors with their entire living.[1]

The fact that the most successful of these actors has begun to believe he can do without them, plagiarising ‘the best of [them]’ with a blank verse play of his own, is little more than an irritated footnote in Greene’s furious diatribe against injustice.

[1] The ‘groat’ of the title was a small coin worth four pence.

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you when there’s new content.