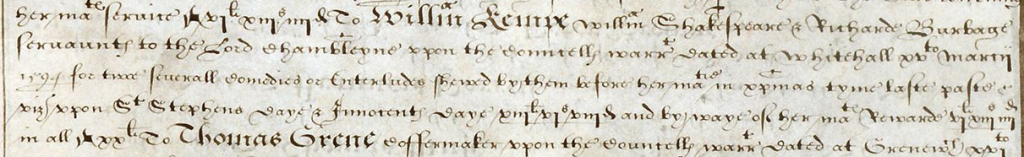

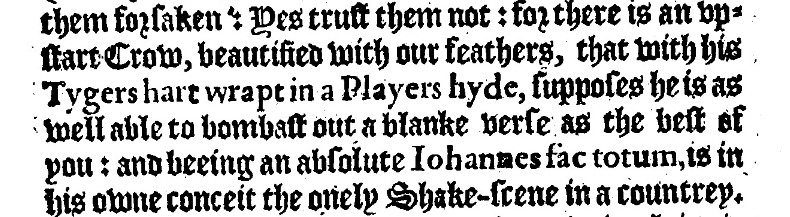

If Edward Alleyn was Robert Greene‘s target, it would certainly be topical, with Tambercam on stage in the months before Greene’s death. Assuming Tambercam was Edward Alleyn’s imitation of Tamburlaine that would also explain why Greene’s letter would address Christopher Marlowe, ‘thou famous Gracer of Tragedians’, primarily (not only addressing him first, but writing more to him than to the other two playwrights), to warn him against the actor who ‘supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blanke verse as the best of you’. Marlowe has been widely acknowledged as the best playwright of this era and was certainly ‘the best’ – and a master of blank verse – when set against Peele and Nashe. The hypothesis that Greene is referencing Tambercam also provides a context for Greene’s plea:

‘let those Apes imitate your past excellence, and never more acquaint them with your admired inventions.’

We know that Greene (and all three of the people he is addressing) wrote plays for Alleyn; it is accepted, for example, that Alleyn played the lead role in Greene’s Orlando Furioso. A large portion of Orlando is among the papers at Dulwich College with additions (early attempts at shaping his own part?) in Alleyn’s hand.

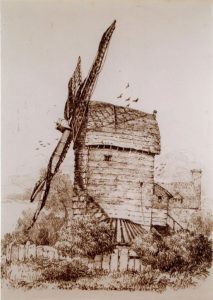

New Find: Alleyn’s Windmill

In the main text of Groatsworth, Robert Greene describes the life of Roberto, whose experience, says Greene, has ‘most parts agreeing with mine’, inviting it to be read as a thinly-veiled autobiography. Greene describes how Roberto met a successful actor, who offered him employment writing plays, with the promise he would be ‘well-paid’. The Player is a wealthy man and Roberto is surprised to discover his profession:

In the main text of Groatsworth, Robert Greene describes the life of Roberto, whose experience, says Greene, has ‘most parts agreeing with mine’, inviting it to be read as a thinly-veiled autobiography. Greene describes how Roberto met a successful actor, who offered him employment writing plays, with the promise he would be ‘well-paid’. The Player is a wealthy man and Roberto is surprised to discover his profession:

‘I took you rather for a Gentleman of great living, for if by outward habit men should be censured, I tell you, you would be taken for a substantial man.’

The Player confirms his wealth and his share-holder status, saying that his share in playing apparel ‘will not be sold for two hundred pounds’ and that he is rich enough ‘to build a Windmill’. Edward Alleyn’s windmill stood on Dulwich Common until 1814.[1] There is no record of Shakespeare ever building a windmill. Had he ever done so, we would certainly know about it.

It is clear that the Player is not only a major shareholder but also the leading actor of his troupe, and he claims to be well-known (‘I am as famous for Delphrigus, & the King of Fairies, as ever was any of my time’). Edward Alleyn seems to have been a sharer in Worcester’s Men from the age of sixteen, and by 1592 (when he was twenty-five), had already become the manager of Lord Strange’s Men.

The Player is a good fit for Alleyn. He is a poor fit for William Shakespeare, who does not appear in the records as a shareholder in any theatre company until after Greene’s death, and was never, as far as we can tell, cast in a leading role.

‘Men of my profession get by scholars their whole living’, Greene has the Player say. That actors depend upon writers for their living, and are beholden to them is a sentiment precisely echoed by Greene in the attached letter just ahead of the ‘upstart Crow’ passage, where he complains of being ‘forsaken’ by them:

‘Is it not strange, that I, to whom they all have been beholding: is it not like that you, to whom they all have been beholding, shall (were ye in that case as I am now)[2] be both at once of them forsaken? Yes trust them not…’

Greene feels ‘forsaken’ by the actors who have benefited from his writing skills and in particular by the ‘upstart Crow’.

Greene Had Already Called Alleyn ‘Crow’

Greene had written against Edward Alleyn before, in his Francesco’s Fortunes (1590), and in terms very similar to those used in Groatsworth:

Greene had written against Edward Alleyn before, in his Francesco’s Fortunes (1590), and in terms very similar to those used in Groatsworth:

‘Why Roscius, art thou proud with Aesop’s crow, being pranked with the glory of others’ feathers?’

Roscius was a famous Roman actor. Scholars agree that Roscius in this passage stands for Edward Alleyn.[3] Here, even though Greene associates Alleyn with Aesop’s crow, the accusation is not one of plagiarism. It is that Edward Alleyn is using words supplied for him by the university wits to gain glory, fame – and importantly, wealth. In Groatsworth, contrasting the playwrights with the upstart Crow, Greene implies that the Crow is an usurer (one who lends at high interest) who has failed to provide for him in his sickness:

‘I know the best husband of you all will never prove an Usurer, and the kindest of them all [actors] will never prove a kind nurse.’

Actors are ‘as changeable in mind, as in many attires’ and as a result ‘Robert Greene, whom they have often so flattered, perishes now for want of comfort.’ His chief concern in Groatsworth is not plagiarism, but money.

That Greene might have expected Alleyn, his wealthy former employer, to come to his aid when he was ill and without other means of income, is not unreasonable. A letter from actor Richard Jones to Edward Alleyn in February of the same year reveals that Alleyn had provided financial assistance to Jones during a recent illness. It opens with ‘thanks for your great bounty, bestowed upon me in my sickness, when I was in great want’.[4] A fair explanation of both Greene’s bile against the upstart Crow, and his sense of being ‘forsaken’, is that Greene, following Richard Jones’s example, had asked Edward Alleyn for money, but unlike Jones, had been turned down.

That Greene might have expected Alleyn, his wealthy former employer, to come to his aid when he was ill and without other means of income, is not unreasonable. A letter from actor Richard Jones to Edward Alleyn in February of the same year reveals that Alleyn had provided financial assistance to Jones during a recent illness. It opens with ‘thanks for your great bounty, bestowed upon me in my sickness, when I was in great want’.[4] A fair explanation of both Greene’s bile against the upstart Crow, and his sense of being ‘forsaken’, is that Greene, following Richard Jones’s example, had asked Edward Alleyn for money, but unlike Jones, had been turned down.

CONTINUE>>>

[1] The London Encyclopaedia (3rd Edition, 2010) by Christopher Hibbert, Ben Weinreb, John Keay, Julia Keay, p.245. This important identifier of Alleyn as Greene’s Player has not been previously noted, to my knowledge.

[2] Greene was dying in poverty.

[3] Alexander 1964, p.68, Shoenbaum, 1987, p.152.

[4] Greg 1907, p.33.

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you about new content.