It is clear from the many legal documents connected to his land-holding, tithe buying, grain dealing, and money-lending, that William Shakespeare was always looking for a way to turn a profit. Is it likely that his natural profit-making and middle-man tendencies ceased when he became involved in the business of theatre? The main product of a theatre company is the performance of plays, and although some might be written in-house, the majority had to be bought from the available pool of writers. As a share-holder, it is reasonable to think that William Shakespeare, a person clearly adept at buying and selling, might involve himself in purchasing suitable texts. Once bought, they belonged to the company.

Though the sum a company could gain from selling a play for publication was only estimated to be around thirty shillings this could nevertheless recoup a proportion of the cost to the company of buying the play from the writer. Thirty shillings is approximately the same sum that Shakespeare went through the courts to recover from Philip Rogers in 1604, so it should not be considered insubstantial. It was a good night’s box office takings for Henslowe at The Rose. A performance of Henry VI on 19 May 1592 brought in exactly thirty shillings, whereas a performance on 11 June 1594 of The Taming of A Shrew (an early version of the play later to become Shakespeare’s The Taming of The Shrew) netted only nine. In addition to a manuscript sale making the company the equivalent of a good night’s takings with minimal effort, the title pages of published plays posted around the city of London as advertisements could function as free promotion for the associated theatre company, who in some cases appeared to have revived old plays to coincide with their publication.

In the Elizabethan period, plays were rarely connected publicly their authors, being associated instead with the theatre companies that owned them. If a play was performed but unpublished — as is the case for just over half of the Shakespeare canon until 1623 — most people would not have known the identity of the author. It would be a century before playwright’s names began appearing on playbills.[1] Throughout the 1590s, it was also common practice for plays not only to be performed anonymously, but to be published anonymously too. Indeed, up until 1594, the year that Shakespeare became a shareholder with the Lord Chamberlain’s men, only one writer — George Peele — had been attributed on the title page of a play originally performed on the public stage.[2] That year, publishing practice changed, and seven out of the eighteen published plays that have survived from 1594 feature an author’s name. By the turn of the century about half of all published plays were still anonymous, but subsequently naming the author became increasingly common. This shift towards publishing plays with an authorial attribution appears to have been linked with a general move by publishers to present dramatic works as suitable for ‘gentlemen readers’ by associating them with an originating author rather than the collaborative process by which so many plays in fact came about.

The diary of theatre-owner Philip Henslowe reveals that from the summer of 1597 to the summer of 1600, sixty per cent (thirty out of fifty-two) of the plays the company bought were co-authored, but in the same period, not a single one of the thirty-two published plays acknowledges more than one author. Less than twelve per cent of the plays published in the forty years from 1584 to 1623 bears more than a single author’s name on the title page. This mismatch may be read two ways. Either co-authored works were rarely of a high enough quality to qualify as readable literature, or publishers were deliberately representing co-authored works as being the fruit of a single mind. Certainly when play extracts were presented in the poetic anthology England’s Parnassus, editor Robert Allott attributed extracts from jointly-authored plays to one author only, generally the more famous one. It may be wise, therefore, to see single authorial attributions not as accurate records of authorship, but rather as a marketing tool that helped to lift the ‘respectability’ of a play into the realm of literature.

A good parallel to the position of the Elizabethan playwright is that of the Hollywood screenwriter. For a start, only people in the industry will generally be aware of who wrote the screenplay of even a very successful movie. Though, unlike Elizabethan plays, films will always give at least one writer credit for the script, screenwriting credits do not always reflect the contributions of those involved. The chief name attached to a screenplay is rarely the only writer and quite often not the originator of the text. The entire screenplay of the 1998 film Ronin was written by David Mamet, but even after arbitration with the Writers’ Guild of America, he was denied a film credit under his own name, being forced to accept it under a pseudonym. And as I will discuss in a future post, there are documented cases where screenwriting credits — and at least one Oscar — have been awarded to someone who didn’t create a single word of dialogue.

Let us, then, add some of these details together. In Shakespeare’s era, a play, once sold to a theatre company, was the property of the company’s shareholders. The text of that play, once sold to a publisher, was the property of the publishers. Writers who were not also company share-holders had no control about how (or whether) their work was sold on. Writers were rarely credited for their works in the period. Even when they were, there was a good chance that co-authored texts would bear only a single name because that was deemed a successful marketing strategy.

No-one knows for certain when William Shakespeare first became involved in the business end of theatre, but the earliest theatrical record citing his name dates from 15 March 1595, in an entry in the Treasurer of the Chamber’s accounts recording £20 paid to the Lord Chamberlain’s Men for plays performed in front of the Queen the preceding Christmas. The payment was made out:

To William Kemp, William Shakespeare and Richard Burbage, servants to the Lord Chamberlain, upon the Council’s warrant dated at Whitehall 15th March [1595], for two several comedies or interludes showed by them before her majesty in Christmas time last part viz St. Stephen’s day and Innocents day.[3]

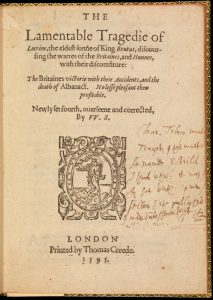

His name as one of the Lord Chamberlain’s ‘servants’ denotes that William Shakespeare, like the company clown William Kemp and lead actor Richard Burbage was, by 1594, a shareholder of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. The company appears to have been founded in the summer of that year; Henslowe’s diary notes performances by The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, alongside those of the Lord Admiral’s Men. Not all actors in the company would be shareholders; some were hired men, paid per performance. But shareholders took a cut of profits and were involved in the business side of things. 1594 was also the year when somebody sold the playscript of Locrine to the printer Thomas Creede; it was entered into the Stationers Register, without an author’s name, on 20 July 1594.

At this point, there were only two publications with the name ‘William Shakespeare’ on them, both long poems. Venus and Adonis had been published the previous June, and The Rape of Lucrece, registered 9 May 1594, was probably on the book stalls by the time Thomas Creede bought Locrine. Both poems were published by Richard Field, a man raised in Stratford-upon-Avon who very likely would have known William Shakespeare. Field’s connection to Shakespeare is a point to which we will return, but one thing is certain; he didn’t publish plays.

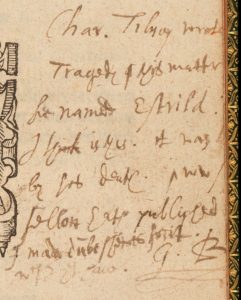

Thomas Creede printed or published a number of canonical Shakespeare plays. In the same year that he published Locrine, 1594, he printed The First Part of the Contention Betwixt the Two Famous Houses of York and Lancaster for the publisher Thomas Millington – a revised version of which would become Henry VI Part 2 in 1623’s First Folio. Henry VI Part 2 and Titus Andronicus were the first plays in the Shakespeare canon to be published. Both were published in 1594, with no author’s name attached. The following year, The True Tragedy of Richard Duke of York (later to become Henry VI Part 3) was the third Shakespeare play to be published, again anonymously; and Locrine was published as being ‘newly set forth, overseen and corrected’ ( you will note, not ‘written’) by ‘W.S.’ It is therefore fair to say that Shakespeare’s career as a published dramatist, and as a person associated with the plays of others, coincided exactly with the formation of The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, in which he was a shareholder.

Thomas Creede printed or published a number of canonical Shakespeare plays. In the same year that he published Locrine, 1594, he printed The First Part of the Contention Betwixt the Two Famous Houses of York and Lancaster for the publisher Thomas Millington – a revised version of which would become Henry VI Part 2 in 1623’s First Folio. Henry VI Part 2 and Titus Andronicus were the first plays in the Shakespeare canon to be published. Both were published in 1594, with no author’s name attached. The following year, The True Tragedy of Richard Duke of York (later to become Henry VI Part 3) was the third Shakespeare play to be published, again anonymously; and Locrine was published as being ‘newly set forth, overseen and corrected’ ( you will note, not ‘written’) by ‘W.S.’ It is therefore fair to say that Shakespeare’s career as a published dramatist, and as a person associated with the plays of others, coincided exactly with the formation of The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, in which he was a shareholder.

It has been argued that the initials on Locrine might be those, not of William Shakespeare, but of minor playwright and scrivener Wentworth Smith. There are a number of reasons for rejecting this possibility. For a start, the only record we have of Wentworth Smith’s playwriting activity begins seven years after Locrine was registered. Smith co-authored fifteen plays for the competing company, the Lord Admiral’s Men, between April 1601 and March 1603. None of these plays were successful enough to survive. But more crucially, Wentworth Smith was never in a position to sell his plays, or the plays of others, for publication. He was not a theatre company shareholder, and it was theatre companies who owned the plays they performed. This play was not Wentworth Smith’s play to sell in any capacity. But it may well have been Shakespeare’s.

CONTINUED>>>

[1] John Dryden notes this new practice with surprise in 1698; Erne p.44.

[2] I am indebted to Lukas Erne’s Shakespeare as Literary Dramatist for many of the statistics in these paragraphs, and have been much influenced in my thinking by his chapter on the legitimation of printed playbooks (pp.31-55)

[3] The record in fact says 1594, but it means 1595 in our modern calendar. The discrepancy is due to the fact that until 1752, the new year officially began on Lady Day, 25 March, rather than 1 January. A vestige of this remains in the fact that the tax year begins on 6 April, which is 25 March adjusted for the days lost when the calendars were changed over.

Click Here to Subscribe and we’ll notify you about new content.

Poor POET-APE, that would be thought our chief,